It’s been another eventful and educational week.

My calf count is up to 44 ID-ed mother/ calf pairs now (with several uncertain pairs to which I may be able to assign IDs after more careful review).

The new calf IDs this week comprised:

- Fataha (#41), accompanied by an escort;

- Faua (#42, male), the second calf with all-white pectoral fins that we’ve photographed this season. Mom also had all-white pectoral fins. This pair were also in the company of an escort;

- Fatolu (#43, female), ID contributed by my friend Douglas Seifert (who has been here with his lovely wife Emily for the past couple of weeks and has been kind enough to contribute valuable calf-sighting information and photographs...thank you!). No escort with this pair;

- Fafa (#44, female), another injured calf with wounds similar to those of Tahafa (#14, male). No accompanying escort.

Faua (#42, male), the second humpback whale calf with all-white

pectoral fins this season. Mommy also has white pectoral fins.

Resightings included:

- Uatolu (#23, female), which I originally ID-ed at Toku Island on 02 September, and Douglas Seifert photographed in Vava’u on 20 September (19-day interval). This is the second example we have documented this season of a mother and calf travelling between the two locations;

- Uanoa (#20, male), accompanied by an escort. We originally ID-ed this calf on 29 August. I subsequently received a photo of this calf from Kristy Peacock, a guest at Mounu Island Resort, taken on 24 August. I photographed this calf again on 24 September (an interval of 32 days from first documented sighting) and was able to determine that the calf is male;

- Tahafa (#14, male), our ninth(!) encounter with this injured calf. We have now documented this calf going from Vava’u to Toku then back to Vava’u, between 23 August to 24 September, a span of 33 days. For a detailed timeline of the first eight encounters, please see Part 6.

Overall, it seems that there are still many whales in the area, including mother/ calf pairs. We have, however, ID-ed fewer new calfs this past week than in previous equivalent periods. This could be due to chance, but I have a feeling that the lower tally may reflect the fact that we’re approaching the tail-end of the season, with an accompanying decrease in the number of births.

One other observation: It may just be my imagination, but there seems to have been a proliferation of singers in recent days. Maybe we’re just noticing more, or perhaps there are actually more whales singing now.

I’d always assumed that the prevalence of singing would be greater during the early part of the season rather than the latter, but maybe I was mistaken. In the past 10 days, we’ve come across 10 singers, and on Wednesday, we came across one of the most complacent and cooperative singers I’ve ever encountered.

Humpback whale calf Uatolu (#23, female), the second calf I've documented travelling

between island groups, thanks to help from Douglas Seifert

Tahafa Back in Vava’u

The big story this week revolves around injured baby humpbacks.

First, there was Tahafa, the injured male calf that I’ve written about extensively in previous posts.

Humpback whale calf Tahafa (#14)

with mom resting in a head-down position

Tahafa has, without a doubt, shaped up to be the star of the season. Over 33 days and through nine encounters, we’ve watched as this little calf has developed from a wee little tyke suffering from grievous bodily harm (see Part 3 for photos) into a happy, healthy young lad full of energy and confidence.

This alone would be amazing enough, but we’ve also now tracked this baby from Vava’u to Toku (accompanied by a long-term escort that mommy seemed to take a shining to) and back to Vava’u again. On 24 September, we again came across mom and baby, this time playing in the inner waterways of Vava’u. We had last seen the pair on 16 September in Toku, some 40km away.

As with our last sighting, mother and baby were not accompanied by the escort that kept them company for at least 14 days (1 to 14 September), suggesting that the parting of the ways I documented as taking place between 14 and 16 September was a permanent separation. (Refer to Part 6 for more details).

The good news is that Tahafa’s injuries seem not to have led to any serious long-term damage. Over the past month or so, the calf’s wounds have healed well:

Tahafa's wounds are generally healing well

In our recent encounters, the young humpback has been extraordinarily playful...tail-slapping, breaching, flopping around...doing all the fun things that baby humpbacks do as they explore their surroundings:

Overcast skies didn't stop Tahafa from enjoying himself

Happy, healthy humpback whale calf Tahafa playing near the surface

At this stage, I’m confident that Tahafa will make it through the season and head south with his mother.

He’s not completely clear of the woods though. The large chunk taken out of the anterior portion of his dorsal fin hasn’t entirely healed over. It looks as if some flesh is still exposed; viewed from the side, the base of Tahafa’s dorsal fin seems to have some tearing.

If you compare the photos below to the image I posted in Part 3 though, you’ll see that the wound appears much better than before, so at least there has been visible healing progress.

Tahafa's wounds are mostly healed, except his dorsal fin,

which still has areas of exposed flesh

There has been some discussion/ speculation about what may have been responsible for these wounds, with theories spanning tiger shark attack, run-in with a boat, and ambush by a group of marine mammals.

Bear with me for a little longer, and I think I can set out a strong case for marine mammal attack, based on a series of images showing similar wounds on three other baby humpback whales I’ve ID-ed this season, and also upon information/ input from a couple of fellow photographers.

The Case for Marine Mammal Attack

Let’s start with the latest calf I’ve ID-ed, a female named Fafa (#44), which we came across on 22 September. Fafa and mother were not accompanied by an escort.

Though not quite as extensive as Tahafa’s wounds, Fafa’s injuries were apparent from the moment I saw her.

This calf was covered with small circular and semi-circular wounds, identical to those on Tahafa. Also like Tahafa, Fafa had multiple wounds distributed all over her body, as opposed to a single wound or wounds concentrated in one place.

Humpback whale calf Fafa (#44, female) re-entering the water after breaching.

Note the wounds all over her body.

Particularly egregious was an injury to the calf’s fluke, with a chunk taken out, resulting in a tear to her right fluke:

Large chunk missing from humpback whale calf Fafa's (#44, female) fluke

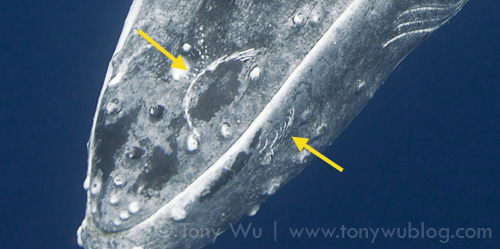

Upon closer inspection of underwater photographs, there are marks that look like an impression left by a bite mark, sort of like what happens when you go to the dentist and he/ she takes an impression of your teeth. The bite marks are all small, suggestive of a relatively small mouth:

These marks on Fafa's mouth look to be impressions left by

the upper and lower jaw of whatever animal attacked this calf

Fortunately, Fafa seemed unfazed by whatever trauma had befallen her, as the calf was playful and brimming with positive energy.

My encounter with Fafa got me thinking about another calf I had seen much earlier this season, Fitu (calf #7, photographed on 18 August).

I posted a picture of Fitu back in Part 2, when I noted the unusual clover-like marking on the calf’s back, magnified in the graphic below. Given the wounds I’ve since seen on Tahafa and Fafa, my belief now is that this clover-like pattern is also the result of attempted bites by a similarly sized mouth.

These marks on Fitu's (calf #7) dorsal surface

look like unsuccessful bite marks

In addition, upon closer inspection of photographs of Fitu, I noticed what appears to be a dental impression on Fitu’s left pectoral fin, again perhaps the result of an attempted bite:

Possible bite impression on left pectoral fin of Fitu (calf #7)

While I was grappling with these data points, we had another re-sighting on 24 September, this time of Uanoa (calf #20, male), with mom and escort.

Uanoa’s mom has a prominent white patch on both flanks, which makes her relatively easy to recognise. The water was murky, skies overcast, and whales on-the-go when we came across them, so I only had one drop to take a look and get photos.

From mom’s white patch, and more importantly...the missing tip of the calf’s left pectoral fin, I was almost certain it was Uanoa, a hunch I was able to confirm later that evening after I downloaded images.

Uanoa (#20, male) is missing the tip of his

left pectoral fin, possibly from a bite

In isolation, the missing tip of the calf’s left pectoral fin might not mean much. But taken together with the wounds and markings on Tahafa, Fafa, and Fitu...I’d say there’s a reasonably high chance that the same type of culprit is behind all of these injuries.

Earlier in the week, Mark Strickland contacted me to suggest that Pseudorca crassidens, commonly known as false killer whales, might be more likely candidates for coordinated attacks on humpback whale calfs than pilot whales (I had previously suggested pilot whales as possible perpetrators).

Mark had an incredible encounter with these marine predators some years ago in Thailand, when he came across a bunch of them hunting sailfish.

To cut to the chase, Mark saw these pack hunters in action, chasing down and obliterating the large fish. A person in the water was stabbed through the leg and abdomen by the fleeing prey and had to be taken to the hospital for emergency treatment of a perforated colon. Fortunately, she made it through OK.

Anyway, given Mark’s direct experience with false killers (and my lack of such experience with them), I took his feedback seriously.

I then asked another friend, Douglas Seifert, for his thoughts, and he mentioned that false killer whale attacks are generally characterised by “raking” marks on their victims. Sure enough, upon close inspection, both Tahafa’s and Fafa’s bodies exhibited such marks.

Example of raking marks on injured calf Tahafa's pectoral fin

Douglas also passed me copies of some peer-reviewed papers about Pseudorca, one of which made reference to another paper that documented false killer whales attacking and killing a humpback whale calf in Hawaii (Hoyt, E. 1983. Great winged whales, combat and courtship rites among humpbacks, the ocean-not-so-gentle giants. Equinox 10:23-47).

So...while it’s difficult to be 100% certain without witnessing an actual attack myself...I believe that the photographs of four injured calfs from this season (Tahafa, Fafa, Fitu, Uanoa), along with the feedback/ input from Mark and Douglas, make the case for a marine mammal attack (probably false killer whales) about as watertight as you can get.

This year certainly isn’t the first time I’ve seen injuries like this on humpback whale babies here, but it’s the first time I’ve had a critical number of well-documented/ photographed subjects to study, augmented by the advice and guidance of two knowledgeable friends.

Sing Me A Song

To round out the week’s experiences, we came across one of the most cooperative singers I’ve ever encountered. Perhaps, in fact, the most cooperative.

In reasonably calm water (with bad visibility unfortunately), this singer adopted the classic head-down pose and remained stationary with fluke at around 10-15 metres for 10-15 minutes at a times. When he came up, the whale didn’t move far, and when he went down again, he stayed shallow.

Most of all, the singer didn’t seem to mind our presence, even though it was clear that he was aware of the pesky little humans hanging around, listening to his solo performance.

One of the most cooperative singers I've ever come across,

in the classic head-down posture

One thing I’ve noticed is that the bass of this year’s song isn’t quite a “booming” as in previous seasons. Even when I hovered directly above this singer, the low notes didn’t reverberate through me quite as strongly as I’m accustomed to.

This has been the case with all the other singers we’ve encountered this year (14 to date), so I assume it’s a characteristic of this season’s tune.