Well...I didn't think it was possible, but my humpback whale calf count for the 2012 season in Vava'u, Tonga has surpassed last year's tally. In 2011, I was able to identify 48 baby whales. As of this writing, I have 52 IDs for the 2012 season!

Humpback whale calf #19 of the 2012 season in Tonga, a bouncing baby boy

I'm sure there were many more out there, as there is no chance that I saw all the babies, or probably not even most of them. Plus...I have a number of calves which I think are different but I'm not sure, so I haven't included them.

But going through thousands of images, re-confirming initial IDs, double-checking location data and uploading to Google Maps, editing photos, formatting my calf count file, writing text, etc. for 52 calves has kept me busy 20 hours/ day for an entire week. I'm pooped.

I had a couple of drama moments, in which I realised I had double-counted one calf, and when I thought I had lost a slew of data. Fortunately, friends sent me more calf IDs to make-up for my double-vision incident, and I found all the data I thought I had lost (turns out...I was just having a premature senile-moment and forgot where I had saved said data).

I have prepared two different files for download. The first is a 17-page, 1MB file that just contains the summary text, graphs and tables. The second is the full file, comprising summary text + photo-ID sheets for every ID-ed calf and comes in at 29MB.

Please right-click the links to download:

Humpback Whale Calf Count 2012 - Summary Only (17pp, 1MB, v1, 04 Nov 2012)

Humpback Whale Calf Count 2012 - Full PDF file, v1 (70pp, 29MB, v1, 04 Nov 2012)

Humpback Whale Calf Count 2012 - Full PDF file, v2 (71pp, 29MB, v2, 11 Dec 2012). Added additional ID of mother of 201217 Juunana. I spotted her with yet another calf (the 4th I've confirmed for her) in the 2009 National Geographic documentary Kingdom of the Blue Whale.

Humpback Whale Calf Count 2012 - Full PDF file, v3 (71pp, 29MB, v3, 13 Dec 2012). Confirmed that the documentary footage is from 2002 via BBC Motion Gallery. See blog post.

In addition, I've uploaded all the location data to Google Maps. In previous seasons, I've split up the map for ID-ed calves and the one for sightings of mother/ calf pairs for which I was unable to establish an ID, but this year, I put them all on one map. They are colour-coded, so it's easy to tell the difference.

The light blue flags represent GPS data. The blue pins represent hand-marked data. The red pins are unknown calf sightings.

View Humpback Whale Calf IDs, Tonga 2012 in a larger map

And just for fun and to underscore the point that the humpback whale females and calves make use of every bit of available terrain in Vava'u, I amalgamated all my recorded encounters for 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012 into a single map.

There are lots of data points, so Google Maps had to split the information into two pages. If you click through and take a look at the data, scroll down to the bottom of the first list of calf data, and you will see the option to click over to the second page.

Please do that so you can see just how many babies visit this area, and how they make use of every nook and cranny available in the island group. To paraphrase: "A Google Map is worth a billion words."

View Humpback Whales 2009-2012, Tonga, Tony Wu in a larger map

If you take the time to read my ramblings and feel the urge to contribute some calf information (calves not in the summary, or additional sightings of calves already in the summary), or if you spot any mistakes, please let me know. I'm hitting the road again soon, but I'll post updates and amendments when I can.

Oh...if you really feel ambitious...I haven't had time to cross-compare the mother/ calf pairs from this season with the ones from previous seasons, so I could use some help in that area.

Nonie Silver spotted a repeat for me in 2009, with a female that had a calf in 2008 as well. By coincidence, that very same female has had a baby this season too (calf 201217), making her the first 3x mommy I've documented. I recognised her in part because Nonie pointed her out to me three years ago (thanks Nonie!).

And finally, in case you are really bandwidth-challenged, I've copied and pasted the text and graphs (no tables though) from the summary below.

Time for a break.

Summary of humpback whale calf encounters, Tonga 2012

Introduction

This document is a summary of encounters with humpback whale mother/ calf pairs in and around the Vava’u island group in the Kingdom of Tonga during the months of July to October 2012.

I use the term “mother/ calf pairs” because my IDs are based on looking at both the adult females and their calves. Baby whales grow and change rapidly in their first few months, whereas body shapes and pigmentation of adults tend to remain the same.

By making the fundamental assumption that an adult female and its calf remain together, i.e., humpback mothers do not swap calves, I can make use of all the physical traits of a given mother/ calf pair for ID purposes. Doing so provides multiple “check points”, so to speak, thereby increasing the odds of making definitive IDs, as well as augmenting the probability of recognising repeat sightings.

One disadvantage of this methodology is the near inability to keep track of the calves after the initial season. If a calf has extraordinary markings or possibly extensive wounds (as was the case with 201114 Tahafa), there is some possibility of recognition after the first season. Barring such obvious physical markers, the calves change too much from the juvenile to adult stages.

My intention with this ID effort is not to track the calves over time, however. The primary goals of this exercise are to:

- Gain insight into the absolute quantity of calves that pass through Vava’u each season (I use the phrase “pass through” because no one knows what proportion, if any, of the calves are born in Vava’u, and my experience to date indicates that most mother/ calf pairs are transient);

- Discern long-term patterns, if any, of relative concentration, movements, locational preferences and density of mother/ calf pairs while they are in Vava’u;

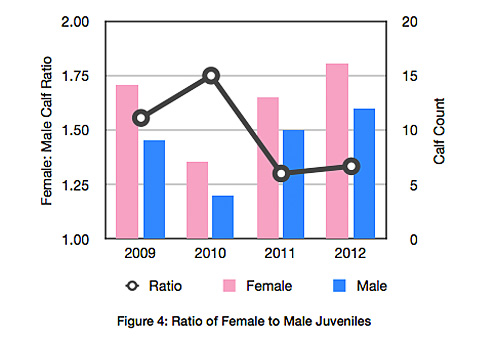

- Keep track of female: male ratio among calves for which I am able to determine sex;

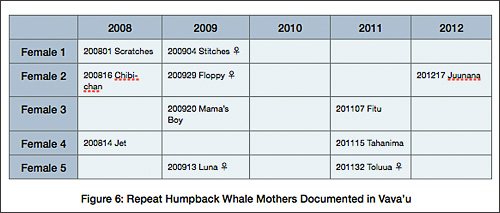

- Attempt to identify repeat mothers in order to gain insight into the frequency of mating and calving;

- Quantify the level of escort interactions with mother/ calf pairs; and

- Record other interesting/ unusual behaviours I see and hear, such as: the sudden appearance of certain obvious physical traits in one season followed by a dearth of that trait in following seasons; the frequent use of vocalisations (not just song) and other sound for communication; heat run competitions among males for females; apparent same-sex intimacy among males; apparent “personalities” of individual whales; courtship behaviour between paired-up males and females; injuries due to both unidentified predators and manmade objects; and other related observations.

As of this writing, I have assigned IDs to 52 mother/ calf pairs for the 2012 season, 31 of which I photographed and ID-ed, with the balance comprising contributions from other people. This exceeds the previous high count of 48 mother/ calf pairs in 2011.

In addition, I recorded 28 mother/ calf pairs for which I had visual confirmation, but was unable to establish ID. Of these 28, I eventually assigned IDs to two, leaving 26 unknown mother/ calf pair sightings.

Highlights from this season include the following points:

- The early part of the season was characterised by unusually favourable conditions. Weather was mostly mild, climate warm, precipitation low, winds low-to-moderate, and underwater visibility excellent. There was however a prolonged drought, so the Vava’u area was suffering from a general lack of fresh water supplies. Toward the latter half of September, precipitation picked up.

- Subjectively, I would characterise overall whale behaviour/ disposition this season as neutral to friendly, similar to the overall mood in 2011 and 2009, and in contrast to that of 2010. There were, of course, exceptions to the general mood.

- The “density” of whales in the area seemed exceptionally high. This is reflected in an elevated Calf/ Boat-day figure and Calf-Sighting Ratio, both of which are significantly higher than the equivalent ratios for previous seasons.

- Once again, the ratio of female to male calves favoured the females. The fact that this has been the case for four years running suggests that this could be the norm.

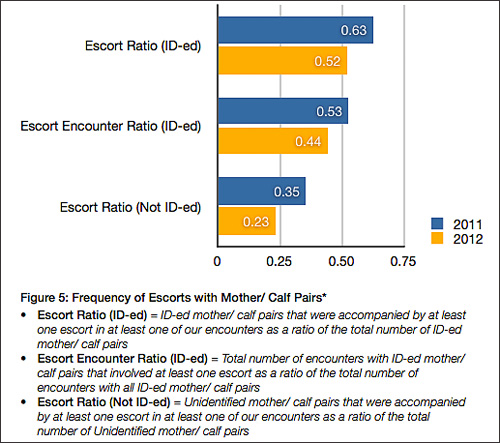

- The overall level of escort activity seemed to be lower than for the 2011 season, as reflected in the metrics I’ve formulated to try to quantify and track the level of escort activity. As this is only the second season for which I have kept records pertaining to escort activity, there is insufficient data as yet to speculate much about possible explanations and/ or implications.

- I did not document any long-term escort associations with mother/ calf pairs, unlike for 2011.

- I documented the first three-time mother to date, with the mother of calf 201217 also being the mother of 200816 and 200929.

- The number of individuals with white pectoral fins was exceptional. I documented 21 such individuals (preliminary figure, subject to spending more time cross-checking), including four mother/ calf pairs with both individuals having white pectoral fins, and another six calves with white pectoral fins. For comparison, I documented two such calves in 2011 (201127 Uafitu and 201142 Faua), and zero in all previous seasons.

- I did not document any calves with the types extensive attack injuries seen on a number of the calves during the 2011 season.

For additional background information from the 2012 humpback whale season, please refer to the following blog posts:

Encounters with Humpback Whales in Tonga | 2012 Season Part 1

Encounters with Humpback Whales in Tonga | 2012 Season Part 2

Encounters with Humpback Whales in Tonga | 2012 Season Part 3

Encounters with Humpback Whales in Tonga | 2012 Season Part 4

Humpback Whale Heat Run

Encounters with Humpback Whales in Tonga | 2012 Season Part 5

Encounters with Humpback Whales in Tonga | 2012 Season Part 6

All of the work referred to in this document has been and is being done on my own time, with my own resources. I do not receive financial or other assistance, and I am not affiliated with any person or organisation involved with cetaceans.

Within this context, I would like to thank the people who have been kind enough to provide photographs, video and related information to help me with this undertaking for the 2012 season:

Jerry Allen

Frank Baensch

Kirsty Bowe

Ray Chin

Ma’ata Fifita

Howard and Michele Hall

Brenda Kaye

Emiko Miyazaki

Takaji Ochi

Douglas David Seifert

For the avoidance of doubt, any errors or silly statements contained in this document are my own, and do not reflect on any of the people noted above.

If you have photographs of humpback whale mother/ calf pairs from the 2012 season in Vava’u that are not included in this file, or additional information about whales already included in this document, please contact me.

Reference documents:

2008 Calf Summary, 2009 Calf Summary, 2010 Calf Summary; 2011 Calf Summary

Methodology

- I recorded GPS locations for all sightings of humpback whale mother/ calf pairs upon initial visual confirmation using a Garmin GPS 72H handheld unit and converted to Google KML format using HoudahGPS. When GPS units were not available, I marked locations by hand on a map.

- Where possible, I entered the water to photograph mother/ calf pairs, escorts and other associated whales if any. I made notes of behaviour, easily recognisable physical traits, and any other noteworthy circumstances.

- When I was able to take photographs of sufficient quality and quantity to establish an ID, I named and assigned a numerical ID to the relevant calf. I downloaded, keyworded and captioned my photos, using Aperture to stay organised. I determined IDs each evening, recorded GPS data, and wrote down notes to minimise passage of time between encounters and assigning of ID.

- In those cases where I was unable to get sufficient photographs to establish ID, I did not name the calves. I recorded the sightings as unknowns and cross-checked any photos of such juveniles with subsequent ID-ed whales to look for possible matches.

- This season, I received more ID photos from other people than I have in previous seasons. I have collected and organised such photos in a separate Aperture library, with relevant metadata, comments, and other pertinent information appended.

- In those instances, I have relied on the relevant people for images, location data and anecdotal encounter information. I have made every attempt to secure such data and information as soon after the relevant encounter as possible.

- I have uploaded all GPS and hand-marked location data to Google Maps, where the locations of all the calves are available for viewing. GPS locations are also embedded as hyperlinks throughout this document when there is text that refers to date and location of sightings. Clicking the hyperlinks will take you to Google Maps to view the relevant location.

- The photographs contained in this document represent a small portion of the images collected. For most ID-ed juveniles, I have additional images for verification purposes.

Observations

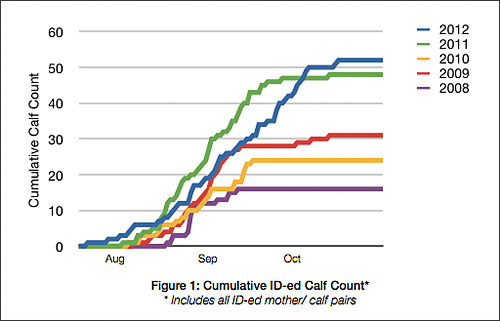

- Figure 1 below illustrates my cumulative calf counts over the past five seasons (incorporating all ID-ed juvenile whales each season, including those contributed by third parties). Once again, the slope of the cumulative calf ID curve appears similar despite inherent differences among seasons (different periods of stay, varying number of boat-days, different number of people helping, weather variations, etc.).

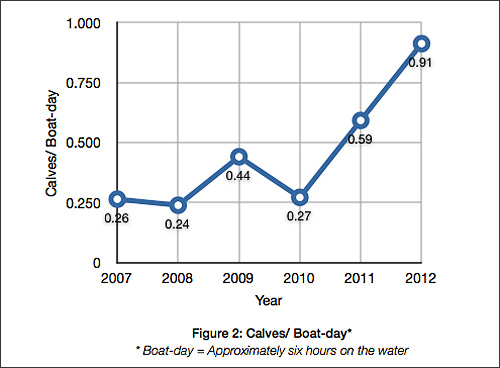

- During my stay this season, I ID-ed 31 mother/ calf pairs over the course of 34 boat-days (compared with 45 calf IDs over 76 boat-days in 2011; 22 calf IDs over 81 boat days in 2010; 26 calf IDs over 59 boat days in 2009; 16 calf IDs over 67 boat days in 2008; 14 calf IDs over 53 boat days in 2007). This worked out to 0.91 Calf/ Boat-day, with a boat-day being defined as a single day of approximately six hours on the water on a boat looking for whales. These figures do not include calf IDs contributed by other people.

- As is apparent from Figure 2 below, this season was exceptional, with the Calf/ Boat-day ratio significantly exceeding the levels recorded in each of the previous seasons. One contributing factor may be that I was only running one boat at a time this season, whereas in previous seasons, I had two boats on the water on many days. This change was precipitated by a number of factors, the most significant of which was consequential damage from the Tsunami on 11 March 2011. This event effectively eliminated visitor traffic from Japan. As a result, the denominator in my Calf/ Boat-day ratio was lower this year than in past years. It would seem logical however that this consideration should have been offset to a large degree, if not entirely, by my inability to cover as much area on a given boat-day compared to previous seasons.

- On a subjective basis, the exceptionally high Calf/ Boat-day ratio for this season is consistent with the high probability and relative ease I experienced of encountering and ID-ing calves this season. There was a noticeably high “density” of mother/ calf pairs, and on balance, a relatively high proportion of those whales were settled, or at least settled enough for me to establish an ID.

- For argument’s sake, if I double the number of boat-days this season from 34 to 68, the resulting Calf/ Boat-day ratio would still be 0.46. In other words, even if there is a measure of positive bias deriving from a reduction in the number of my boats, an over-simplistic doubling of my boat-day count still results in a very high figure.

- Taking this season’s Calf/ Boat-day ratio together with those of previous years, there is a wide band, ranging from 0.24 in 2008 to 0.91 this season. This suggests to me that the Calf/ Boat-day figure may fluctuate substantially from year-to-year. In other words, there may be no “norm” for expected mother/ calf pair density.

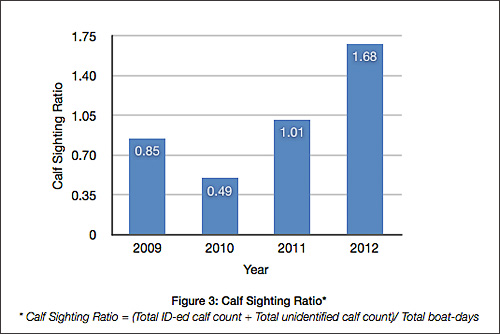

- Moving on, Figure 3 on the following page depicts the total Calf Sighting Ratio for 2009 to 2012, where I have defined Calf Sighting Ratio as = (Total ID-ed calf count + Total unidentified calf count)/ Total boat-days. Once again, for consistency with previous seasons, I only took into consideration the whales I identified and not those contributed by other people. The ratio for this season was 1.68 (would be 0.84 if I doubled the boat-days), which compares with 1.01 for 2011, 0.49 for 2010, 0.85 for 2009. This ratio provides a reasonable indication of the overall level of humpback whale mother/ calf pair activity in the Vava’u area, and, once again, the high level this season is consistent with my experience on the water.

- We again found mother/ calf pairs scattered throughout the entire topography of the Vava’u Island group. Please refer to this Google Map.

- As was the case in both the 2011 and 2010 seasons, there were not many calf sightings this year in North Bay; in contrast, there were quite a few in 2009. This season, there were also relatively few encounters in the main channel between Hunga and Nuapapu; there are normally many more in this area.

- Each season, there seem to be areas that are relatively popular among the mother/ calf pairs. The “in” places change, so statements applicable to the 2012 season may or may not have relevance to any other season.

- Within this context, it is worth underscoring the point that extrapolating from limited observation from limited days in any single season to draw conclusions about the dynamics of the humpback whale population that visits Vava’u is inadvisable, at best. Only long-term observation and consistent recording of data may eventually reveal underlying patterns and trends.

- Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is to amalgamate my mother/ calf pair sighting data for all ID-ed and unknown mother/ calf pairs for 2009-2012 (the period for which I’ve been keeping track). Please refer to this Google Map to see the result. Note: There is so much data that there are two pages to the map, scroll down to the bottom of the list of baby whales to click to the second page and see the complete sighting map.

- The reason I wish to highlight this is that each season, I come across people making sweeping statements about whales in Vava’u. In most cases, such statements reference doom-and-gloom, are seemingly intended to foment discord, and are backed by no data. Particularly disappointing are individuals purporting to represent large, multinational NGOs who make unsupported, disparaging statements about the whales and whale-watching in Vava’u. The above-referenced map should demonstrate beyond a shadow of a doubt that humpback whale mother/ calf pairs make abundant use of every area of Vava’u. Facts count. Zealotry does not.

- This year’s sightings once again supports my notion that, for the most part, humpback whale mother/ calf pairs use Vava’u as a transit area, visiting for a limited duration before moving on, returning to the area at a later date in some instances. Within this context however, there were a handful of repeat sightings over extended periods of time, as there have been in previous seasons:

- 201209 Kyuu (2 encounters/ 10 days);

- 201212 Juuni (2 encounters/ 10 days);

- 201217 Juunana (2 encounters/ 26 days). 3x mother - see below;

- 201221 Nijuuichi (2 encounters/ 37 days);

- 201224 Nijuuyon (3 encounters/ 13 days);

- 201226 Nijuuroku (2 encounters/ 21 days); and

- 201235 Sanjuugo (3 encounters/ 21 days).

- The ratio of female to male juveniles once again favoured females. This has been the case for four years running. This year, we counted 16 females and 12 males (13 females and 10 males in 2011; 7 females to 4 males in 2010; 14 females to 9 males in 2009). Given the consistency of these sex-ratio records, I am discounting chance and other possible explanations, and leaning toward the conclusion that there may be a slight bias in female births to males among southern hemisphere humpbacks.

- The escort ratios this season were all lower than they were last year, as is apparent in Figure 5 below. Out of 52 ID-ed mother/ calf pairs, 27 were accompanied by escorts in at least one encounter with the relevant mother/ calf pair, a ratio of 0.52. Out of 68 total encounters with those 52 ID-ed mother/ calf pairs, 30 encounters involved at least one escort, a ratio of 0.44. In the case of unidentified mother/ calf pairs, the ratio was 0.23. I only calculated one ratio for unidentified mother/ calf pairs because we had only one encounter with each pair.

- Taken at face value, this seems to suggest the possibility that the ratio of eligible/ interested males to females already with calves could have been lower this year than it was last year. Possible contributing factors might include fewer males in the area (could they have gone elsewhere?); males heading back south relatively early (mated and lost interest early?); more single females than last year (though that might be difficult to reconcile with the high number of females with calves); less cooperative/ willing females with calves this year; and probably more potential considerations that have eluded me. In any event, it will take more observation and data collection to see what, if any, pattern might emerge.

- It is interesting to note that the Escort Ratio for the Unidentified mother/ calf pairs is lower than that for the ID-ed mother/ calf pairs in both 2011 and 2012. Common wisdom has it that the presence of escorts makes it more difficult to have successful encounters with mother/ calf pairs, the rationale being that escorts “push” mother/ calf pairs to keep moving. My own experience suggests that there is little to no such relationship, and that escorts “calm” mother/ calf pairs as often as, perhaps more than, they “push” them to move. Some females also seem predisposed to avoid contact from any species. It will be interesting to see if this disparity in the Escort Ratio between the ID-ed and non-ID-ed mother/ calf pairs remains constant going forward.

- Unlike the 2011 season, I did not document any long-term associations between escorts and mother/ calf pairs.

- Despite the lack of opportunity to document any long-term escort relationships this season, I did have an interesting observation relating to escorts. On two occasions (involving calf 201233 and calf 201242), there were males that appeared to be challenging one another for the right to claim primary escort position with the respective females. As the battles ensued, the males appeared to become so preoccupied with their competitive displays that they forgot about the females. The males traveled further and further from the mother/ calf pairs as they continued to jostle for dominance, until they completely lost track of the females, leaving the respective mother/ calf pairs in peace. I cannot recall ever having witnessed this type of behaviour before, but it is certainly possible that I did, but did not take notice, given that I really only became interested in escort behaviour last year.

- On 28 September, I witnessed and photographed a group of three male whales engaged in intimate behaviour. The first time I recorded such seemingly amorous interaction among males was in 2010. In that case, there were also three males involved. I have observed and photographed many intimate episodes between male and female humpback whales. In both 2010 and this year, the interaction among the male whales could easily have convinced me that male/ female courtship was taking place. I have learned that it is necessary to confirm visually with photos or video the sex of all whales involved in seemingly intimate interaction, as there is obviously some role for same-sex intimate behaviour among humpback whales. It is very tempting and easy for an inexperienced person to jump to conclusions. See this blog post for more details on this fascinating topic.

- One of the most rewarding aspects of keeping track of the mother/ calf pairs is documenting repeat mothers. This year marked the first three-time mother that I have documented to date. The mother of 201217 Juunana is also the mother of 200816 Chibi-chan and 200929 Floppy. There may be more repeat mothers among this year’s mother/ calf pairs. I have not yet had time to compare all of this season’s mothers with all of the mothers in previous seasons.

- I witnessed in the water for the first time two mother/ calf pairs socialising. They swam side-by-side, with the mothers in the middle and calves on the outside for five to ten minutes. The mothers interacted; it did not seem that the babies were permitted to do so. I was unfortunately unable to take a photograph, but I hand-drew a diagram of what I witnessed (see this blog post).

- There was an exceptional number of whales with white pectoral fins. As of this writing, I have documented 21 such individuals (subject to additional review when I have time). Among those whales are four mother/ calf pairs with both adult and baby having white pectoral fins, and another six calves with white pectoral fins. For comparison, I documented two such calves in 2011 (201127 Uafitu and 201142 Faua). Last year was the first time I documented calves with white pectoral fins, and this season, there were at least ten. There were also many other adult whales with white pectoral fins and with partial white pigmentation on their pectoral fins, many more than I’ve noticed in other seasons. I am interested in the sudden appearance and disappearance of obvious physical traits such as white pectoral fins because I believe they may be indicative of underlying genetic closeness. If this were to be the case, and if these traits appear in clumps, then there may be the possibility that individuals travel to some degree in tandem with relatively closely related whales. There is, to the best of my knowledge, no other information or evidence to suggest that this happens.

- A simple way to test this possibility would be to biopsy a number of whales with similar physical traits when they appear in substantial numbers within a single season and test for genetic similarity. There are at least two issues that make this difficult. First, it is impossible to predict in advance which physical traits will appear in large quantities in a given season, so it is impossible to know in advance which trait(s) to look for. Second, I do not have access to biopsy equipment or genetic laboratories. Keeping track of obvious physical traits is the best I can do for the time being. If and when I get sufficient time, I hope to go back through my archives and pick out all the whales with white pectoral fins (and split dorsal fins) for past seasons, in order to see if I can discern and document any patterns.

- I did not document any whales with split dorsal fins this season. There were two calves (201210 and 201216) with notches in their dorsal fins, and calf 201217 has a somewhat unique double dorsal fin.

- One of the babies with white pectoral fins, calf 201243, was not accompanied by its mother or any other adult whale. Given that juvenile humpbacks are entirely dependent upon their mothers for sustenance and protection, this calf most likely did not make it. I have seen abandoned/ lost calves in other instances, so this is perhaps not unusual. There was also a calf that stranded in Ha’apai earlier in the season. A number of people worked together to re-float that whale, but again, without its mother, a humpback calf has no chance for survival.

- Calf 201242 appears to have acorn barnacles (Coronula diadema) all over its body, with discolouration of skin appearing in patches where the barncales are most concentrated.

- A number of the babies also exhibited “scrape” wounds, for lack of a better term. I have noticed these in past seasons, but have not kept meticulous records. These wounds are characterised by scrape-like patterns along the dorsal area, between the dorsal fin and fluke. Most often, these wounds are on both sides of the body, and only affect the top ridge of the body, almost as if someone used a brillo pad or steel wool to scrape down the length of the calf’s body. Some adults also exhibit this wound pattern. I am certain that these are wounds and not pigmentation, as I have seen and photographed fresh wounds with scrape/ cut marks still bleeding. I have no idea what causes this, and am at a loss to imagine a scenario explaining these wounds, but they appeared on calves 201219, 201230, 201232, 201237, 201241, 201242, 201247.

Cumulative humpback whale calf count in Tonga,2012

Humpback whale calves identified per boat-day, Tonga

Total calf sightings per boat day in Tonga

Ratio of female to male humpback whale calves in Tonga

Humpback whale escorts with mother/ calf pairs in Tonga

Humpback whale females with calves in multiple years, Tonga