My previous post about the hydrozoan Spirocodon saltatrix seemed to strike a chord.

As many mentioned in feedback I received, hydrozoans can indeed be beautiful to behold. They can also pack a punch too though.

There is perhaps no better example than the infamous Portuguese man o'war (Physalis physalia), also called the bluebottle. Known as katsuo-no-eboshi (カツオノエボシ) in Japanese, this hydrozoan is sometimes referred to as denki-kurage (電気クラゲ), where denki means electricity and kurage means jellyfish. It's a perfect description.

To get an idea of what it feels like to get hit, imagine doing this: Licking your finger. Shoving it into an electrical socket. Then having someone pound said finger and other random body parts with a sledge hammer half a dozen times or so and once again sticking your finger back into the electrical socket. (Obviously, do not do this!)

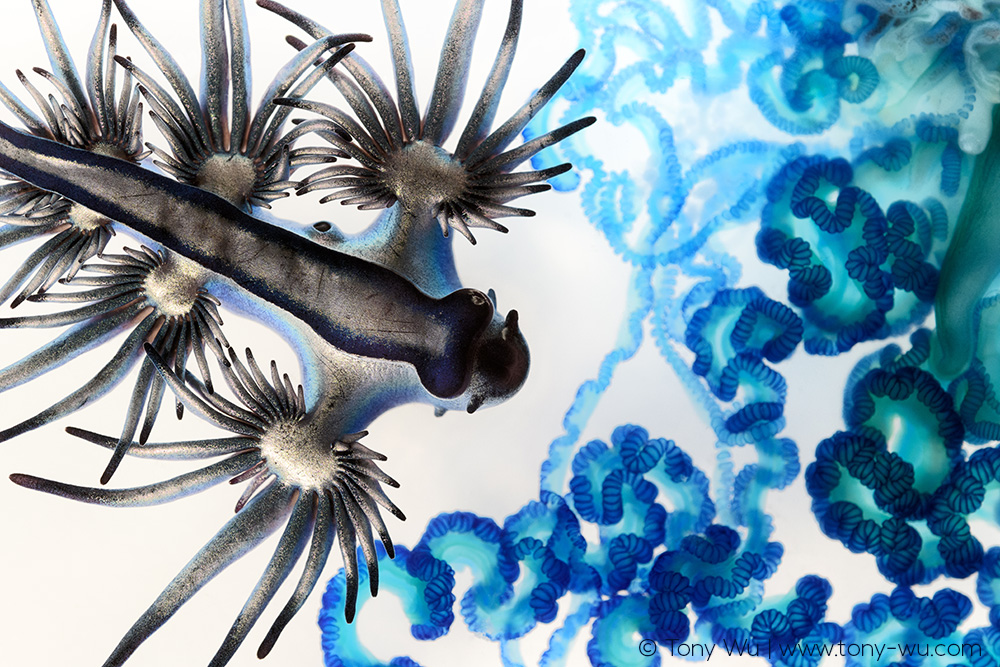

Note the intricate beauty of the nematocyst arrays. Viewed from above, the air balloon (pneumatophore) that this colonial animal uses to stay afloat looks almost like a head, reminiscent of the xenomorph (Internecivus raptus) from the movie Alien.

As painful as getting stung can be, there is only one confirmed fatality due to bluebottle sting that I can find, from an incident in 1987 on the Atlantic coast of Florida. (1) I have been stung multiple times, so clearly there is no long-term damage (Peanut gallery - hush!).

The photo above is from a mass stranding of Physalia physalis hydrozoans. It happened in South Africa back in 2017, when the winds and seas were wicked-high for many days, blowing everything onshore. When conditions eased, the beaches were covered with hundreds of thousands—maybe more—of these gelatinous beings. It was impossible to walk anywhere without stepping on many.

Some were in good condition, remarkable considering the intensity of the storms that had brought them to land. With no prospect of being able to head to sea any time soon, I decided to photograph this floating nemesis of mine.

But how?

With nothing but my friend Stevie's kitchen at my disposal, I MacGyver-ed a makeshift studio using disposable chopsticks (watching Stevie use chopsticks was Asian-parent-cringe comedy gold, though he's since improved because we sent him training chopsticks for kids - we're proud of you Stevie!), paper, cardboard, tupperware, dishes, aluminium foil, paper clips and other random knickknacks. I had buckets of seawater as well. And Marlin, Stevie's most excellent Swiss Shepherd friend as my assistant (never mind that he kept howling and knocking things over).

There is an entire community of animals that live in the open ocean together with bluebottles, including blue sea dragons (Glaucus atlanticus), pelagic nudibranchs that roam the ocean.

These pelagic sea slugs float upside-down by making use of surface tension to cling to the underside of the ocean surface. How's that for a trick?

They prey upon Portuguese man o'wars and other siphonophores, and—get this—they recycle the stinging cells they've ingested by distributing them throughout their bodies for self-defence. Many nudibranchs appropriate the weapons of their victims for their own use, but looting stingers from bluebottle is arguably in a class all its own.

Other critters in the blue-water community washed up as well, including a violet sea snail (Janthina janthina), another mollusc that lives in the open ocean and preys upon hydrozoans.

These sea snails create their own flotation by encasing air in mucous. They float along and stick out their loooong heads to chomp on yummy hydrozoans. They are sequential hermaphrodites—beginning life as males, becoming female along the way. I am not sufficiently versed in Janthina anatomy to have figured out which this one was.

There was also this crab, which I think is a Columbus crab (Planes minutus):

This species lives in the Atlantic, often among Sargassum weed. They also seem to associate with sea turtles, loggerheads in particular, and might even clean the turtles. (2)

This one was blue and among the other blue-community animals that washed up, so I'm guessing that this one lived in open ocean.

I am writing about this now because I'm landbound again, stuck waiting for unfavourable conditions to let up. I spend a lot of time like this, especially since I've started concentrating on temperate and colder seas. Weather in these parts is fickle, so biding time is just part of the game.

I do my best to make use of downtime. Sometimes it's reading. Sometimes planning. Sometimes just sleeping to catch up with much-needed rest. In this instance in South Africa, I had the opportunity to learn about animals that I probably would have never otherwise been able to observe so closely.

_________________________________

(1) Stein, Mark R et al. Fatal portuguese man-o'-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Volume 18, Issue 3, 312 - 315.

(2) Frick, Michael & Williams, Kristina & Bolten, Alan & Bjorndal, Karen & Martins, Helen. (2009). Diet and Fecundity of Columbus Crabs, Planes Minutus, Associated with Oceanic-Stage Loggerhead Sea Turtles, Caretta Caretta, and Inanimate Flotsam. Journal of Crustacean Biology. 24. 350-355. 10.1651/C-2440.