Among the books I've read that have left a lifelong impression on me is one that I came across by accident, while browsing through a leftover box in a second-hand bookstore — Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, written by Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki. The core concept of the lectures contained in the book, if I may oversimplify, is that one should approach life with the innocence and open-mindedness of a child’s first inquiry.

Next time you’re in the company of a toddler, watch the curiosity, eagerness and delight with which the child investigates the simplest of objects — a spoon, a table, whatever — and you’ll get the general idea. By opening up your mind as a child does, and by avoiding the “expert syndrome” that plagues too many all-knowing adults, you’ll see more, learn more, understand more — and hopefully gain insight into the core essence of whatever you’re facing.

Though it's been perhaps twenty years or more since I last read the book, I recently found myself contemplating Suzuki-san’s teachings once again, during my first dive trip in Japan.

Dive Japan. Seriously?

Japan isn’t a popular dive destination, in the sense that Manado, Bali or Sipadan are. In fact, I’d wager that most of the international diving community knows very little, if anything, about diving in Japan.

There are, however, many excellent dive destinations, ranging from tropical waters in the south to ice diving in the north, with temperate environments in between. With such a diversity of climates and habitats, the variety of marine life is staggering.

Despite having studied, lived and worked in Japan for many years, I never took time to dive here. Why? I forgot the lessons I learned from reading Suzuki-san's words.

You see, divers in Japan generally aspire to travel abroad to idyllic locations like the Maldives, Palau, PNG, etc., so quite naturally, my Japanese friends are envious of the fact that I get to travel to places like this all year.

You see, divers in Japan generally aspire to travel abroad to idyllic locations like the Maldives, Palau, PNG, etc., so quite naturally, my Japanese friends are envious of the fact that I get to travel to places like this all year.

Common wisdom dictates that diving abroad (from the view of someone in Japan) is far better than diving domestically. Most of the diving in Japan is, after all, in temperate conditions (this means cold!), where waters can tend toward being green and/ or dark.

I made the mistake of accepting this common wisdom, without questioning it with a “child’s mind”.

In all fairness to myself, much of the reason was my lack of enthusiasm for entering what I perceived to be extremely cold water (anything below 28º C is frigid!), but as I re-learned in recent weeks, closing one’s mind and accepting what everyone else “knows” to be true is almost always a mistake.

Dumb and Dumber and Dumbest Descend on Japan

What got me here in the first place was a request by my friends Kelvin Aitken and Saul Gonor to help them arrange a dive trip to Japan. Kelvin runs Marine Themes, an excellent stock library of marine images. He and Saul were eager to visit Japan to photograph local marine life, particularly sharks, rays and deepwater fish.

My primary qualification for helping them out was the fact that I speak Japanese and know lots of people in the Japanese dive community. I was forthright with my admission that I’d never dived in Japan (with one minor exception of a few days down south in tropical waters, which really doesn’t count), and also with my overwhelming lack of desire to don a drysuit and voluntarily step into what I deemed to be water too cold for any sensible human.

Kelvin and Saul, being anything but sensible, decided in any case to proceed. One thing led to another, and the three of us ended up in the Usami area of Ito city, which is on the eastern coast of the Izu Peninsula.

Kelvin and Saul, being anything but sensible, decided in any case to proceed. One thing led to another, and the three of us ended up in the Usami area of Ito city, which is on the eastern coast of the Izu Peninsula.

For the geographically challenged, Izu is reasonably close to Tokyo, about one to two hours away, and it’s probably the most popular/ easily accessible dive destination for Japanese divers in the Tokyo area.

For two weeks, we based ourselves in a small minshuku (local inn) in Usami, where we slept on futons on the floor, feasted on lots of fresh fish caught by local fishermen (At least Kelvin and I did. Poor Saul was less keen on fish, though he deserves kudos for managing to adapt over the course of the trip), and generally made our presence known in the Izu dive community.

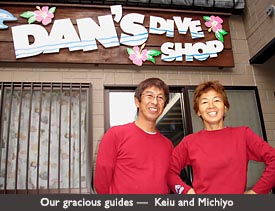

Our kind and extremely patient hosts were Keiu and Michiyo Suzuki, who ferried us around, answered questions and otherwise babysat the three intrepid gaijin dumped onto their front step.

Keiu and Michiyo worked with Masuda-san, who was the foremost authority on marine life in this part of Japan until he passed away recently. The couple have authored an excellent guidebook on the nudibranchs of Izu, and they seem to know everyone in the area. Keiu has also discovered a species of basslet, which carries his name — Rabaulichthys suzukii.

Keiu and Michiyo worked with Masuda-san, who was the foremost authority on marine life in this part of Japan until he passed away recently. The couple have authored an excellent guidebook on the nudibranchs of Izu, and they seem to know everyone in the area. Keiu has also discovered a species of basslet, which carries his name — Rabaulichthys suzukii.

Suffice it to say that the success of our trip is due primarily to Keiu’s and Michiyo’s hard work, assistance, and seemingly limitless capacity to handle our endless queries and requests.

Fortune’s Unseasonal Smile

I’m not a big believer in omens and such, but it sure seemed like the stars were aligned for us.

In the days leading up to our trip, the weather forecast seemed unstable, and I was worried that we’d end up getting smacked by a typhoon (we were at the tail-end of the typhoon season), which would’ve put a serious damper on things. As it turned out, the day we arrived in Izu was the first day of precisely two weeks of excellent conditions, marred only by one windy day. Amazingly, the day after we finished our trip was the first day of several days of bad weather. Impeccable timing!

Next, Saul had forwarded a list of species that Kelvin and he were hoping to photograph. Most of the fish were relatively rare, and it was the wrong season for those that weren’t. Bummer. As a consequence, we were conceptually prepared for the possibility of being skunked, but clearly we were hoping for the best.

First dive into the water, within three minutes or so, Keiu spotted one of the animals on the list — a Japanese angel shark (Squatina japonica) — which posed quietly for us for over an hour! Without going into too much detail, let’s just say it only got better from there.

First dive into the water, within three minutes or so, Keiu spotted one of the animals on the list — a Japanese angel shark (Squatina japonica) — which posed quietly for us for over an hour! Without going into too much detail, let’s just say it only got better from there.

Day-after-day, species-after-species showed up, despite the fact that most weren’t supposed to be around. Keiu, who dived on most days with us, was in utter disbelief at our luck, and Kelvin and Saul — well, let’s just say they were as giddy as a couple of giggly Japanese schoolgirls (though unfortunately nowhere nearly as cute).

If you’ve never dived Izu (as I’m assuming most people haven’t), it might be a bit difficult to understand just how incredible our luck was. The Izu Peninsula is located in a temperate climate, meaning that there are four distinct seasons on land and in the water. This fact alone makes the diving here entirely different from what you’d experience in tropical waters, where the conditions are largely the same year-round. Of course, there are changes on tropical reefs too, but you don’t get waters ranging from 11ºC to 25ºC.

On top of this, oceanic trenches surround Japan, which means that Izu is affected by periodic changes in deepwater currents. Cold water from down deep at certain times of the year brings nutrients and a unique community of marine life, for instance.

Finally, the Kuroshio, which is a warm-water current similar to the Gulf Stream, bathes the Izu Peninsula during parts of the year, bringing tropical marine life to the area.

The sum result of this complex aquatic algebra is that divers in Izu see everything from ghost pipefish to deepwater anglerfish. What you see depends upon when you dive, though, so you won’t see ghost pipefish in the dead of winter, but you will in the autumn.

Nearly all the animals on our want-to-see list are typically winter/ spring visitors to Izu waters, and we were diving at the beginning of autumn. Of course, it wasn’t categorically impossible to find and photograph the fish we were looking for, but we most certainly beat the odds.

Nearly all the animals on our want-to-see list are typically winter/ spring visitors to Izu waters, and we were diving at the beginning of autumn. Of course, it wasn’t categorically impossible to find and photograph the fish we were looking for, but we most certainly beat the odds.

Staying Dry

One of the biggest personal challenges for me on this trip (other than enduring two weeks solid with Kelvin and Saul!) was using a drysuit. This was my first real experience with a drysuit, and the sum total of the instruction I’d ever received on drysuit diving was a few words from my friend Jim Thiselton in South Australia, who offered me this advice: “It’s easy. Go down, and when your balls hurt, put more air in the suit.”

Based upon two weeks of practical experience diving with a drysuit, here’s a list of the five main issues I encountered with drysuit diving (my apologies to cold-water divers who already know this stuff):

1. Getting the %$@%$*! suit on. From now on, I’ll never complain about getting into a wetsuit again. Checking and putting on a drysuit is a much more involved process than donning a wetsuit, the main reason being, of course, that you’re supposed to stay completely dry. Any leaks would mean getting water into the suit, which would entirely defeat the purpose of the suit, and even worse, could be dangerous. Drysuits have built-in boots, meaning that there’s no easy way for trapped water to get out. Having water in your drysuit weighs you down, making it difficult to ascend. You also need more weight than you do with a wetsuit, so everything’s a lot heavier and cumbersome than when you dive in warm water.

2. Keeping the drysuit dry. There are just so many ways for a drysuit to leak. There are many types of suits, but they all have some things in common, like (incredibly constrictive) seals around your neck and wrists, a watertight zipper, and one-way valves for dumping air. When these work well, you stay dry and toasty on the inside. When something doesn’t work, you’re as sorry as a cat in the rain. I had the misfortune of spending one entire hour-long dive in a drysuit filled with water (one of the valves leaked). Trust me…not at all pleasant.

3. Maintaining neutral buoyancy. With so many ways for air to move around the suit (and also your BCD if you use one), drysuit diving can be a bit tricky. If you try to hang head-down, for instance, all the air in your suit rushes to your suit legs, which inflate like balloons, while the seal around your neck clamps down like a vise. Reorienting yourself can be a challenge too. After two or three dives, I got the general hang of it, but I wasn’t beyond suffering a few embarrassing moments from time-to-time. Learning to use your dump valves at the right time is the key.

4. Ascending in a controlled and graceful manner. Every diver knows not to ascend too quickly. When you’ve got a drysuit on, your entire suit is a huge air bladder, which means you’ve got to be extra careful to ascend carefully. It’s much easier to dump air from a BCD than it is from a drysuit. I found that it was easiest for me to dump a little air at a time all the way up. You can set your dump valves to automatic to help, though you’ve got to be in the correct position for air to escape.

5. Ignoring nature’s call. Speaking of large bladders, perhaps the most excruciating aspect of drysuit diving is being unable to pee. There are ways around this (I tried but failed to get photos of Kelvin in his diapers), but since I was using a borrowed drysuit, I had to exercise self-control, which meant no coffee in the morning, and enduring a few dives during which I had to exercise Zen-like discipline to prevent leaking, so to speak.

When all was said and done, I stayed dry most of the time, didn’t notice the water temperature, and had great dives.

I did end up at the surface feet-up, head-down, hanging like a razorfish at the end of my first dive, though I had already surfaced and so wasn’t in any particular danger. All things being equal, I decided that it was better to assume a more standard and less-embarrassing configuration, so I was sincerely grateful for Keiu’s assistance to get myself un-discombobulated.

I did end up at the surface feet-up, head-down, hanging like a razorfish at the end of my first dive, though I had already surfaced and so wasn’t in any particular danger. All things being equal, I decided that it was better to assume a more standard and less-embarrassing configuration, so I was sincerely grateful for Keiu’s assistance to get myself un-discombobulated.

Thankfully no one was around to capture that particular Kodak moment.

I should mention that the water temperature ranged from 19ºC to 22ºC during our trip, so we could have dived with really thick wetsuits. Many of the local divers were using thick wetsuits, though quite a few were in drysuits too.

While I would have enjoyed the relative freedom of movement with a wetsuit, in hindsight I’m happy that I learned how to use a drysuit in relatively easy conditions, and not in absolutely frigid waters. In theory, I should be ok now to explore even colder waters, now that I’m comfortable with drysuit diving. In theory.

Dinner Conversation

With the relatively cold water and with the way things are set up in Japan, two dives a day was the limit for us, usually around an hour apiece. We dived all around the Izu Peninsula, so we had to travel quite a bit. By the time we returned to our minshuku each day, there was usually just enough time for a quick shower before having dinner.

Dinner was always a big deal — sashimi, grilled fish, fresh vegetables, tempura, miso soup, etc. Japanese inns usually serve two meals a day (breakfast and dinner) for guests. The meals are included in the price of a night’s accommodation, and everything is fresh, handmade and would cost an absolute fortune in Tokyo.

Dinner was always a big deal — sashimi, grilled fish, fresh vegetables, tempura, miso soup, etc. Japanese inns usually serve two meals a day (breakfast and dinner) for guests. The meals are included in the price of a night’s accommodation, and everything is fresh, handmade and would cost an absolute fortune in Tokyo.

Dinner was also a time for reflection on the day’s events and brainstorming (I use the term ever so loosely) with Kelvin and Saul about the next day’s strategy.

And of course, part of the joy of travelling with two such distinguished companions was the sophisticated dinner conversation.

For instance, sitting down to the evening meal after another day of success during which we found a baby Japanese bullhead shark (Heterodontus japonicus), Kelvin picked up a bowl of yummy Udon noodles and observed:

“The nice thing about Japan is that you’re allowed to slurp.”

Not to be outdone by this incisive cultural comment, Saul duly added, “In fact, you’re expected to.”

After a slight pause, during which I duly slurped my noodles, Kelvin concluded this particular part of the night’s discourse with the closing comment: “It’s like burping in Arabia or farting in Saskatoon.”

Saul happens to be from Saskatoon…

Happy Halloween

This is a bit of a digression, but I have to make a point of saying that I finally got to see and photograph one of the fish I’ve been dying to see for as long as I can remember — a dragon moray eel (Enchelycore pardalis).

Why precisely I’ve been so smitten by this eel I can’t really say, but perhaps it has something to do with the elongated fish’s gaudy colouration or the “horns” on its heads. These eels can be found all over Izu, so divers in Japan generally don’t bother with them. In fact, all my Japanese friends find it highly amusing that I can be so enthralled by such a common critter.

Why precisely I’ve been so smitten by this eel I can’t really say, but perhaps it has something to do with the elongated fish’s gaudy colouration or the “horns” on its heads. These eels can be found all over Izu, so divers in Japan generally don’t bother with them. In fact, all my Japanese friends find it highly amusing that I can be so enthralled by such a common critter.

For me, however, coming across my first dragon was exhilarating. And the fact that my first encounter was on Halloween day seemed oddly appropriate, given the brown-and-orange motif of the eel’s body, as well as its somewhat goblin-like visage.

While reviewing my photographs of this amazing animal, I realised that the eel has a third row of teeth, pointing backward, on the roof of its mouth. No doubt this is to help secure its prey and prevent escape. Gulp.

More About Izu

Japan has always been a fishing nation, and Izu is one of the largest fishing areas. As a consequence, fishermen are king here, so areas where diving is permitted are limited and diving times are restricted.

For most of the areas on the east coast of Izu, you have to be out of the water by 3:00 pm, which isn’t that big a deal in the autumn/ winter, when it gets dark early, but I could see it being a pain when there’s more daylight. For most of the west coast, you have to be out by 4:00 pm.

To the west is the relatively deeper water of Suruga Bay, so the western side of the peninsula is where you’re more likely to find deepwater fish that come up seasonally from several hundred metres to dive-able depths. The eastern side seems to have more cartilaginous fish (sharks, rays). If you get a chance to visit, try to dive both sides of the peninsula, as you’ll have entirely different experiences.

Accommodation-wise, there aren’t many dive resorts per se. Visitors generally stay in minshuku like the one we stayed in or something equivalent, and travel to dive areas each day. Logistically, this means a lot of packing and unpacking, as well as hauling around of gear and cameras.

Accommodation-wise, there aren’t many dive resorts per se. Visitors generally stay in minshuku like the one we stayed in or something equivalent, and travel to dive areas each day. Logistically, this means a lot of packing and unpacking, as well as hauling around of gear and cameras.

Minshuku rooms are relatively small, and it’s usually two to a room. You sleep on futon mats on the floor, and baths are communal (male/ female separate of course). Space is at a premium in Japan, so there’s not much area to lay out your camera gear and other junk. The chances of finding an easily available internet connection are slim.

There’s an element of making-do and putting-up with available conditions, so it can be a bit of a hassle, but that’s the way things work here. The food, of course, is mainly Japanese, meaning lots of fresh seafood, fruits and vegetables. There are certainly places you can get a burger or pizza...but why?

Diving is structured and organised, as is typical of most things in Japan. At first glance, this might turn a lot of people off, but as Kelvin perceptively pointed out one day, there are certain advantages to this.

Diving is structured and organised, as is typical of most things in Japan. At first glance, this might turn a lot of people off, but as Kelvin perceptively pointed out one day, there are certain advantages to this.

You’ll find facilities like hot water, rinse tanks, and maps of the area with the locations of critters of the day accurately marked. Dive guides from different shops share information so everyone gets to see what they want. The cooperative atmosphere was quite refreshing given some of the antagonistic relationships I’ve seen in other destinations.

In fact, by the end of the first day, most of the dive community knew we were here, and people were telephoning-in information to us about dive sites, animals, etc. — as efficient as a Toyota production line.

Bottom line — If you visit with the right expectations, you can have a really good time, as we did.

Once we got our bearings, everything went really smoothly (as things tend to do in Japan). And somehow or another, even when there were quite a few divers around, we always had plenty of time to observe and photograph what we wanted without being disturbed.

We mostly did shore dives, at the sites are well marked and there's plenty of marine life. Depending on the location, there are quick drops to the deep blue, or shallow, sloping sand areas. Overall, dive conditions were not difficult, the major challenge being toting gear back and forth to/ from the entry/ exit points. Currents were mild, visibility was reasonably good, and underwater topography easy to remember.

As a general rule, one thing you don’t want to do though, is dive on weekends or during a Japanese holiday. Most popular dive sites will be packed with divers. There are some places you can go which will be less crowded even during these times, but it’s better to dive weekdays and take time off to look around on weekends.

Other Experiences

Aside from diving, we were treated to a tour of the Awashima Marine Park, which has a nice collection of deepwater fish on display. The head of the facility was kind enough to spend a couple of hours showing us around and telling us about some of strange fish and other creatures from the deep they've seen.

We also spent some time with local fishermen, who let us peek into their hauls from several hundred metres down. We found all sorts of interesting animals, like chimaeras, hagfish, sea cucumbers, anglerfish and much more.

My personal favourite discovery was a deepwater sea spider, which was so creepy that it could've come straight off the set of the movie Alien. Way cool. The sightless hagfish were hideous too, as were many of the other fish that I still can't identify.

Fishermen are a colourful lot in any country, and the fishermen in Japan are no exception. In one instance, after about 45 minutes of conversation, one fisherman was surprised to learn that I’m not Japanese. He spent the next few minutes loudly announcing his discovery to the other fishermen. Fortunately, we were well acquainted enough by then that everyone found it quite amusing.

We sampled local amaebi shrimp fresh off the boat, and were treated to lots of fresh sashimi. Perhaps the most unique culinary experience of the trip was deep-fried lionfish. As unappetising as it sounds, the dish was absolutely delicious.

Needless to say, the venomous portions of the fins were removed, but other than that, every other part of the fish was edible — nothing went to waste. Even Saul, who was the least seafood-adventurous among us, enjoyed the unusual dish.

Needless to say, the venomous portions of the fins were removed, but other than that, every other part of the fish was edible — nothing went to waste. Even Saul, who was the least seafood-adventurous among us, enjoyed the unusual dish.

Just so you don’t get the wrong impression, lionfish isn’t something that’s normally served. This is a specialty dish that only a few places prepare. The chef at the particular restaurant we visited happened to be a friend of a friend, and is also a keen diver and underwater photographer.

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

At some point early in our Izu adventure, I realised just how much I had underestimated the diving here. By automatically adopting commonly accepted opinion and my own preconceptions, I had closed my mind without giving Izu a fair chance.

Determined not to let that mistake in attitude continue, I spent the trip marvelling at everything — from the tiniest goby to the most unusual deep-sea creature, from the simplest observation that Kelvin, Saul or I made to every bit of information the local guides shared with us.

Determined not to let that mistake in attitude continue, I spent the trip marvelling at everything — from the tiniest goby to the most unusual deep-sea creature, from the simplest observation that Kelvin, Saul or I made to every bit of information the local guides shared with us.

It’s beyond my capability to put into words just how much I saw and learned, and how incredibly engrossed I became with every aspect of the seas around Izu.

I never thought that I would be saying this, but I’m eager to dive Izu again…when it’s colder. Winter and spring bring colder water to Izu, and the influence of the Kuroshio wanes, meaning lots of strange deepwater animals appear.

If you’re interested in exploring Izu, drop me a line and let me know. I’m sure I’ll be visiting again soon. Poor Keiu and Michiyo, who must be gluttons for punishment, said they'd be happy to have us back any time. They may yet live to regret saying that!

As always, I'm way behind on looking through my images and processing them. I'm sure I'll never get through them all, but I've uploaded some to my Flickr page and will endeavour to upload more in the coming days.

Finally, my sincere thanks to the following people, who helped tremendously with this trip: Aquaforum, BlueQuest, Dan's Dive Shop, PNG Japan, TUSA, Zillion, and of course to Kelvin and Saul, who've no doubt left a lasting impression on Izu.