The ocean is replete with drama.

Romances, thrillers, comedies and tragedies transpire without our knowledge, masked by a hypnotic, aqueous barrier that transfixes, yet impedes human perception.

The only way to bear witness to such submerged stories is to plunge into the sea with open senses and objective mind, becoming…for however brief a time…part of the undersea world.

In the context of where I am now, this means that a precondition for understanding the natural history of humpback whales is spending time in the water.

I’ve spent more than a decade now watching baby humpback whale calves around Vava’u in the Kingdom of Tonga. Photographing them, taking notes, recording data, writing seasonal summaries…and connecting dots where I can, all with the hope of gaining insight into their lives, the challenges they face, their happy moments, even their occasional misfortunes.

Over time, I’ve worked out many common threads and recorded a number of unusual events. These days, one of the greatest pleasures I have during the humpback whale calving season is figuring out mini-dramas as they play out and relating them to my friends who travel to Tonga with me.

Seeing a humpback whale calf in the water is an amazing experience; understanding a piece of a juvenile cetacean’s life story makes such an encounter all-the-more rewarding.

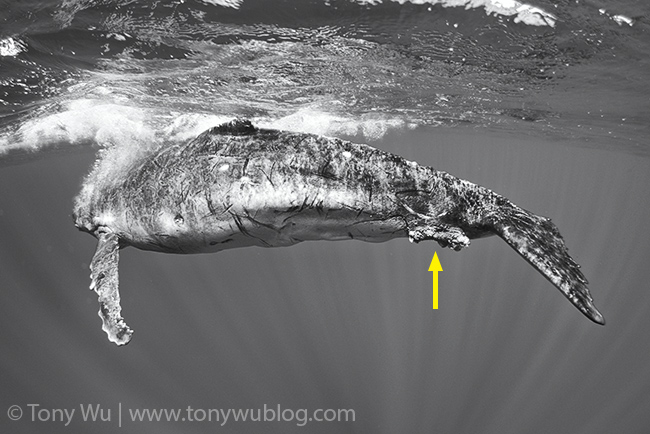

Take the calf above for example.

It’s a little boy. One that I have encountered only once as of now, on 26 August.

He is too skinny for his size, clearly underweight. He’s covered in scratches, marks and scars.

He has what appears to be a gaping wound at the base of his peduncle, on the left side just above his fluke. I’m not sure what caused the injury; my best guess (from examining photos) is that something took a big bite and thrashed around, twisting and contorting newborn flesh.

But you know what?

For all that this little boy has been through, he’s happy, adventurous, and above all…energetic. Here is incontrovertible proof:

So what we have here is an underdog (or perhaps an underwhale?).

The calf has had a tough time. His ragged wound and abundance of scars are testament to this, as is his below-average mass.

If one were to consider his size, weight and injuries in a clinical sense, it would be easy to proffer the view that the calf’s chances for survival are low. But that would be a mistake.

At first contact, this calf swam directly to me, a good 20–30m away from his mom, showing little to no hesitation. Perhaps that spunky attitude is what got him in trouble previously, but whatever trauma occurred in the past clearly hasn’t dented his vigor and zest for life.

As if to hammer this point home, the calf breached, and breached, and breached, and breached, and breached while we watched…forcing his mother to stir from her slumber and accompany him, joining in at times with impressive aerial acrobatics of her own.

This calf is a survivor. Of that, I have no doubt.

26 August also saw another episode in a cetacean mini-series unfold, this one particularly rewarding because I forecasted it last week.

In Part 3 of my updates from Tonga this season, I detailed part of the story of female calf 201415 and her mother.

In short, I first ID-ed the mother/ calf pair on 19 August when the adult seemed wary and agitated; re-encountered them in the AM on 20 August when mom rejected the advances of a would-be escort; and then came across them for a third time in the PM of the same day, this time with a king-sized escort and three challengers in pursuit.

My contention was that this series of events (a) demonstrated the adult female entering a period of estrus (with attendant male attention), and (b) showed that the males had worked through the bulk of eligible single females and were devoting increasing attention to females already with calves.

I conveyed all of this to my friends here at the time, with the concluding comment that I’d really like to see this mother/ calf pair again in a few days. My bet was that if we were fortunate enough to have such a reunion, she would once again be without escort, and that in fact, no males whatsoever would be interested in her.

The reason? Because within a short time, she would’ve passed through estrus, and the boys would’ve lost motivation.

Well, that seems to have happened by 26 August.

We had a reunion with calf 201415 and her mother on that date. And just as I predicted, they were alone, sans pesky boys with ulterior motives.

In normal seasons, to the extent there is such a thing, I’d have far fewer potential opportunities to observe connected events like this. I’ve seen this happen before, but when there are as many whales around as there seem to be this season, chances for making critical natural history observations of this sort are optimal.

The final little drama I’d like to share with you this week relates to calf 201405, another little girl. Or actually, not quite so little now.

My first encounter with this calf and her mom was on 11 August, followed by a re-sighting the next day. Thereafter, nothing…until 29 August.

I mentioned in an earlier post that many mother/ calf pairs seem to be sticking around the islands for extended periods of time this season, more than I’d usually expect. Calf 201405 is a perfect example.

The calf has clearly grown a lot since our earlier meetings, a positive sign for sure. She’s also gained a lot of confidence, demonstrating a penchant for executing tail slaps and associated flourishes.

From the standpoint of observations about humpback whale behaviour though, two points stood out for me from the repeat encounters with this mother/ calf pair.

First, they were without escort during both earlier meetings. On 29 August however, an escort was with them, a laid-back male who was unconcerned by our presence. The company of an escort for this mother/ calf pair further reinforces the trend toward an increasing ratio of escort-accompanied female/ calf pairs as the season progresses.

Second, he breached.

I’ve heard many people ask why humpback whales breach. I’ve heard even more explanations, many of them butt-stupid.

For example, early on in my history with humpbacks, a tour operator here told her clients that whales breach only because they are being harassed. This led to a lot of agitated people, some on the verge of emotional hysterics as they pointed fingers at a friend and me, accusing us of being evil, evil people for harassing whales.

Sadly, there are still people who make such obtuse statements, causing unnecessary consternation for all concerned; there probably always will be.

There are many reasons why whales breach. In this instance, my view is that the male breached to show off. His entire body cleared the water, full bulk remaining suspended for a moment before crashing down flat-out on the ocean surface, resulting in a deafening thunderclap.

By maximising his altitude and the surface area smacking the sea, the male made the loudest sound possible, punctuating his point. Sound is the communication medium of choice underwater, so a resounding crash like this would carry through the water with great efficiency, communicating the whale’s size, strength and fitness to anyone in the vicinity.

Well…it just so happened that a pair of whales (likely male) was approaching at the time.

The escort breached once, sending a message that was loud and clear: Approach at your own risk. The pair decided that discretion is the better part of valour and elected not to engage the big boy, skirting the periphery instead.

With the ocean just chocked full of whales this year, I’ve seen this type of behaviour play out multiple times.

In another memorable instance, I was also able to live-narrate play-by-play as this happened with calf 201410 on 15 August. We watched as another escort breached with his entire body out of the water just before two challengers came charging in at super-high speed.

In that case, the would-be usurpers didn’t heed the escort’s warning, but lost anyway. With a few well-placed body blocks, kicks and slaps, he sent them scurrying for cover. One of the pair slapped the surface of the ocean with his flukes repeatedly, expressing agitation before the pair of interlopers departed.

My calf count stands at 23 now, of which 10 are female, 7 male, and 6 unknown. The males are gaining ground, but the females still lead.

I’ve ID-ed 22 of the 23 calves myself. So with 19 days on the water now, that’s a ratio of 1.16. Although still at an all-time high, my calf/ boat-day ratio continues to decline, going from 1.41 to 1.26 to 1.16 now over the course of my posts to date (my previous all-time high was 0.91 for the 2012 season).

There are still a lot of whales around. Subjectively, I think the gradual decline in this ratio is indicative of the fact that many mother/ calf pairs are staying in the area. More specifically, I am re-encountering many calves that I’ve previously ID-ed. I’ve had 16 re-encounters to date.

Spending time with re-encounters of course takes away from time spent searching for and ID-ing new calves.

My white pec count stands at seven individuals now, with one re-sighting (an adult female that is the mother of female calf 201408).

My split dorsal fin count stands at three, which is a lot.

Having both white pecs and split fins here in number at the same time is unusual. I can’t recall this happening before, though I’m relying on memory, not records, so I could be mistaken. As if to underscore this point, we came across a pair of whales traveling together, probably males, on 25 August. One was a white pec, the other a split fin.

For a humpback whale geek like me, that’s like hitting 777 in Vegas. Twice!

Finally, this past week saw the departure of one group of friends and the arrival of another. I’m fortunate to have such great friends from around the world joining me. Positive group dynamics are critical for having an enjoyable time, fostering an atmosphere conducive to relaxation and learning.

Can’t wait to see what the coming days and weeks bring!

Related Posts:

Humpback Whales in Tonga 2014 | Part 1