This has been the year for heat runs.

As of the time I’m writing this, I’ve spent 13.5 boat-days at sea looking for humpback whales. In that time, I’ve seen seven heat runs, eight if I include the rampaging six-whale heat run I just saw in Neiafu Harbour this morning. (Whales do come into the main harbour from time to time, but a heat run? It’s probably happened before, but I’ve never seen it.)

I don’t have to look through my records to know that this is the highest concentration of heat runs I’ve experienced here. I usually expect to see a handful each season, but certainly not eight(!) within my first couple of weeks at sea.

Moreover, the competitive groups this year have been real doozies…that’s technical-speak meaning jam-packed with mind-blowing, out-of-this-world action. It’s been all-out pec-slapping, bubble-blowing, body-slamming, tail-whacking, guttural snorting, full-contact chaos.

I love it!!!

“What is a heat run?” you might ask.

In short, it’s a bunch of boys competing for the attention of a girl, the same thing that happens with most other animals. Only in this case, we’re talking about a tremendous amount of mass…40+ tonnes per animal multiplied by lots of whales. The biggest group I’ve seen to date comprised at least 10 whales, the smallest four.

I say “at least” because when the action is fast-and-furious, it’s often impossible to be certain of the number of whales involved.

Counting whale breaths from the surface is a fool’s errand. There’s simply no way to make sense of the pandemonium with accuracy.

Even in the water, it’s difficult to keep track. Limited visibility means you can’t count individuals that are too far or deep to see at any given time. And heat runs are a dynamic phenomenon; whales often enter and break-off from the fray in revolving-door fashion. Plus, you have to keep up…no simple feat when the whales are in a hurry.

So when I say “at least” ten whales, that means I have photographic proof of ten whales at a given time, though I’m sure there were more involved.

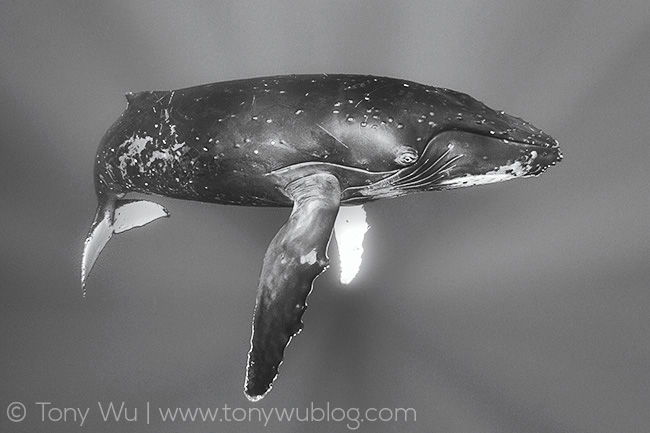

Take this photo for instance:

There are seven humpback whales in it. One is mostly hidden below the main two, so difficult to see. The one on the right with the white belly and black dots showing is the female. All the others are male suitors.

For this heat run, I can definitively say that there were seven whales, because I can point to seven in the above photo. But I also know that there were maybe twice that number in the immediate vicinity, cycling in-and-out.

If I were to take thousands of photos and invest time to ID each whale, I’m sure I’d end up with more than just seven. But I didn’t take that many pictures, and I don’t have the time or desire to try to figure out exactly how many there were. All that’s important is that the heat run involved a heckuva lot of horny humpbacks!

Competitive groups like this revolve around a single female.

When the female is alone (i.e., without a calf), she seems to know and revel in the fact that she is the center of attention. A female in this role twists and twirls as she swims…teasing the hormone-crazed boys, inducing them to follow her if they can and slug it out to see which one wins the right to mate.

There are usually one or two males that are true contenders for top-spot. I’m not sure why the other whales (i.e., ones that don’t appear to stand a chance of winning the battle for the female) participate in these competitive groups. Perhaps it’s for practice or fun, or maybe they’re hoping for a long shot at success, the cetacean equivalent of a Hail Mary pass.

In the at-least seven-whale heat run shown above for example, there were two primary contenders, the bubble-blowing baleen pictured below, and the whale with the white pectoral fins at the beginning of this post.

This dark whale and the white-pec male were always the ones closest to the female. They jockeyed nonstop for pole position, blowing bubbles often to show dominance and aggression. They slammed into one another with flukes, pecs, and occasionally even with full body-blows punctuated by audible thwacks.

One reason I love heat runs so much is that no two are the same.

There are certain basic principles, but specific inter-whale dynamics are different in each case. In addition, there’s interplay with terrain, and the mood can change substantially with ambient conditions.

Like all good shows, there are times of peak action, periods when subtle shifts in individual ranking cause plot upheaval, and even intermissions, when the action slows or comes to an eerie standstill.

Of particular interest, 20 August marked the first heat run that I’ve seen this season centering upon a female with a calf.

Some background: As I speculated might happen in my previous update, the number of escorts accompanying females with calves has increased.

Out of 19 calf IDs I have at this point, 10 have been accompanied by at least one escort, compared to 5 out of 14 at this time last week (52.6% vs. 35.7%). The ratio now is more in line with what I’d expect based on the numbers I’ve calculated from past seasons here.

The probable reason for this increase is that the randy boys have worked through most of the single females, and are starting to pay more attention to female humpbacks that already have calves.

In the case of female calf 201415 and her mom, this led to an all-out competition on 20 August.

I first ID-ed this mother/ calf pair a day earlier, on 19 August. They weren’t particularly friendly, and they were alone, i.e., no escort present.

The next day, we came across the pair again at 10:40 and watched as the female rebuffed a would-be suitor, resulting in the exasperated male departing from mother and calf, breaching three times in rapid succession to express his frustration (men the world over can relate I’m sure).

Later in the day, at 14:15, we came across the same mother/ calf pair again, this time accompanied by an enormous escort, which was being challenged by three other males…in other words, a heat run.

We had witnessed a mini-whale-drama unfold over two days…a mother/ calf pair minding their own business were approached by at least one male that the adult female rejected, then by a very big male that she accepted as her escort. The escort then had to defend his position against at least three challengers who wanted to displace him as the female’s escort.

Two questions come to mind.

- Why would the males pursue a female with a calf?

- Why would so many males suddenly decide to pursue a given female at the same time, when they had all left her alone the day before?

The answer to the first question is easy. They want to mate.

It is definitely possible for a female humpback to give birth in two consecutive years. I have photographic proof of this happening here.

To put this in context though, it’s probably not a regular occurrence, as it’s metabolically taxing (what an understatement) to give birth to a 4-metre, many-tonne baby and raise it while fasting. I’d imagine a rational female of any species wouldn’t want to do that twice in a row.

Still…it does happen, which suggests that it’s worth some investment of time and energy on the part of males to pursue females with calves…after they’ve knocked up the single females of course.

Now…just because a given male wants to mate, and the relevant female lets him hang out with her and her calf doesn’t necessarily mean that the boy gets what he wants in the end. The fact that most females don’t show up in consecutive years with babies underscores this.

It is however a fundamental law of the universe that if there’s even the slightest hope of getting some action, boys will do whatever it takes, however low the odds.

That’s my entirely non-scientific, but rational explanation of why males bother with mother/ calf pairs.

Which then begs the second question: Why so much attention at once?

I’ve seen the all-the-males-in-a-given-area-piling-on-and-harassing-a-single-female-with-calf-at-the-same-time thing happen enough times to know that it’s a pattern. Other females in the area are often left undisturbed while multiple males vie for position as escort to a single female already with calf.

At first blush, it might seem more logical for the boys to split up, each taking different females.

Unless, of course, timing is critical.

I believe that females with calves that find themselves at the center of a heat run are entering a period of potential fertility, i.e., estrus. The males somehow know it, and concentrate their efforts on the female that is in heat, so to speak.

I have no hard proof for this narrative (like biopsies to measure hormone levels), but I have seen this scenario play out over and over, and on the back-end, I’ve seen mother/ calf pairs that had 10 or more males fighting over the adult female on day X have exactly zero males paying attention to her on day X +1 (which would suggest the female’s period of estrus had passed).

Circumstantial evidence, certainly. But consistent enough that I can often live-narrate multi-day dramas like these to friends who’ve traveled to Tonga with me.

Stray thoughts to wrap-up for this week:

My calf count stands at 19 calf IDs right now, 17 of which I’ve ID-ed myself during 13.5 boat-days, for a ratio of 1.26. The ratio now is slightly lower than it was last Sunday, but still exceptionally high. Any way you cut it, there are more calves here than I’ve ever experienced.

Last week I wrote about split dorsal fins, noting that they are one of the relatively rare physical characteristics that I look for to identify individual whales. Another such trait is white pectoral fins.

They aren’t as rare as split dorsal fins, but they’re not common here by any means. In most seasons, I see a few or none. Then in some seasons, I get a whole bunch. Could be coincidence, but I think there’s something underlying this feast-or-famine trend.

The most I’ve ever recorded in a single season is 21, back in 2012. This year, I have 5 so far, including the bubble-blowing male at the top of this post. The others are two adult females, a male calf, and another adult whale in a heat run (probably a male, but I don’t have photos to assign gender with 100% confidence).

Some day (when I have time…sigh), I’ll collate all the white-pec photos I have and assign IDs. Whether there are repeat sightings or not, it’ll be interesting, as all things Megaptera-related are.

Related Posts: