It’s been another eventful two weeks or so since my last major update, starting with an unanticipated return visit from my friends aboard Bella Principessa.

Shortly after posting my last update, I received an sms saying something to the effect of: “Please book a table for dinner at 19:30.”

The thing is…my friends were supposed to be in Ha’apai by then, so naturally, I was perplexed. More to the point, I was concerned for their safety.

At dinner, I learned that 50-knot winds coupled with large(!) swells conspired to punch out one of the escape hatches on the underside of the catamaran. Generally speaking, having a hole in the bottom of your vessel isn’t a great idea, as a sudden influx of seawater tends to ruin vacation plans.

It took my friends 1.5 hours or so to figure out a way to stem the incoming tide and then head back toward Vava’u. Fortunately, when all was said and done, everyone was ok, and the boat ended up being fine after a few repairs. Whew!

The next day, a group of travel-weary friends arrived from Thailand. A bit of settling in, and we hit the water the following morning.

We came across a rampaging six-whale heat run right away, certainly not the easiest introduction to humpback whales!

The mood, as it were, of heat runs varies. Sometimes the participating whales are inquisitive; at other times they scatter at the first hint of humans.

In this case, it was more toward the latter (probably an 8 or so on a difficulty scale of 1 to 10), though I did manage a few good looks, good enough in fact to make eye contact with the lead female and watch her spin around and display.

It was challenging for my jet-lagged friends though, particularly since this was their first experience with whales. Swells and choppy seas didn’t help either.

Fortunately, we had a series of easier encounters over the following days…namely, six humpback whale mother/ calf pairs, one of which was accompanied by a singing escort. (The song this year has a lot of booming, reverberating bass!)

So…even though I’m not doing my calf count this year…I am sorta’ keeping count. Old habits die hard.

From what I’ve seen so far, this season seems like it might end up being unusual in a couple of ways.

First, while there seem to be relatively few whales around viz. the past few seasons, there are quite a few mother/ calf pairs in the vicinity. In other words, it’s looking like we may have a relatively high concentration of mother/ calf pairs, even though the overall number of whales seems low.

Somewhat counterintuitive, no?

My experience in past seasons has been that the frequency of encounters with mother/ calf pairs has reflected the overall number of whales in the area, i.e., lots of whales = many mother/ calf pairs; fewer whales = fewer mother/ calf pairs.

Such a positive correlation makes more sense to me than what we’re experiencing this season, but whoever said humpback whales or Mother Nature need necessarily do what we expect?

Bearing in mind that I took a time-out for two+ weeks to chill with friends (so there’s a hole in my data), I’ve now hit the water 15 days, and I have 10 ID-able mother/ calf pairs. That’s a 0.67 ratio, which is pretty darn high!

The equivalent ratios were 0.91 for the 2012 season and 0.59 for 2011, both of which were banner years with lots and lots of whales around.

I’m scheduled for another 14 days on the water in the coming weeks, so it’ll be very interesting to see how this pans out.

The second head-scratching trend to appear from the data I’ve recorded so far is that there have been more male than female babies.

For the past four seasons, the sex ratio of baby humpbacks has favoured females, ranging from around 1.30x to 1.75x females: males. Of course, I’m not able to determined the gender of every baby I see, but I had started to think that in the world of newborn humpback whales…females > males was the norm.

Again, it’s possible that my two+ week vacation earlier in the season has somehow had an effect. As of now, I have 5 males and 2 females (out of 10 total ID-able babies), equating to a ratio of 2.5x males-to-females.

Perhaps the most interesting encounter for a whale geek like me though, didn’t involve getting into the water at all.

A few days ago, we watched a lone humpback whale, probably male, engage in behaviour that seems to suggest that it was feeding.

Why would this make me skip around like a hyperactive kid who just scarfed down way too many sugar-glazed donuts?

Well…humpback whales aren’t supposed to be feeding in their winter calving/ breeding grounds.

Accepted wisdom stipulates that humpbacks only feed during the summer months (down in the Antarctic in the case of the whales that visit Tonga), while devoting their winter months to breeding, calving, nursing and associated activities.

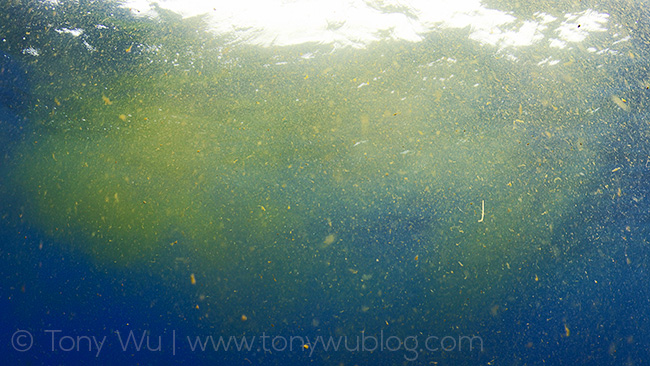

I’m sure this is generally true, but here’s the thing…over the years, I’ve seen adult humpback whales poo, like this:

And this, from 30 August this season:

Seeing Megaptera emissions like this on multiple occasions has led me to wonder why adult whales would have a need to defecate if they aren’t eating. Shouldn’t it stand to reason that if an adult whale poos, it must have ingested something and processed it into poo?

In other words, “What comes out must have gone in,” right?

And not gone in months ago, but gone in recently.

To the best of my knowledge, there is no conclusive evidence demonstrating that humpbacks in either hemisphere eat during their respective winter seasons (if you know of any such evidence, please clue me in!), but I have discussed the possibility with other experienced/ credible people here in the past, and I’ve heard multiple accounts of what sounds like feeding behaviour.

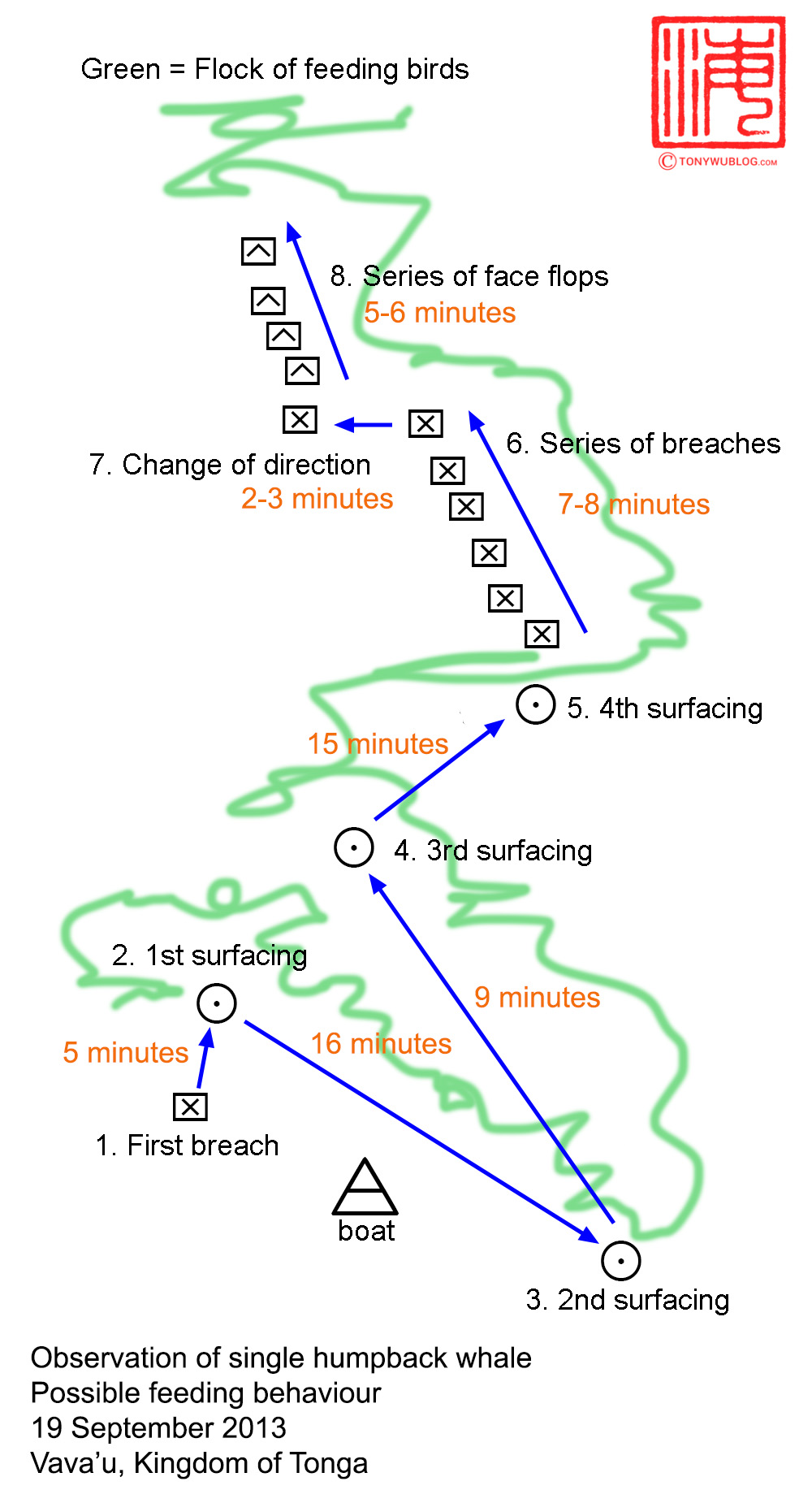

On 19 September, I saw such behaviour myself (woohoo!!!!!), illustrated below:

In short, a lone humpback whale followed the course of a flock of birds feeding on bait fish. Each time the whale surfaced to breathe, it appeared right smack in the middle of the birds and fish.

Then, toward the end of the hour+ period of observation, the whale executed a series of breaches and forward face-flops that seemed to drive/ steer the fish, much as fishermen slap the surface of the water to herd schools of fish into nets.

The birds tracked the whale’s actions (or vice versa) the entire time. And when the birds finally dispersed, the whale also broke its pattern of behaviour and wandered off.

(See photo of possible humpback whale feeding)

The way I look at it, there are three possible explanations for what we saw:

- It was pure coincidence, with absolutely no relationship between the actions of the whale and the birds;

- For some strange reason, humpback whales and birds play together for extended periods of time just for the heck of it, and the fish that the birds were feeding upon were irrelevant;

- The correlation between the whale’s and birds’ movements reflect the fact that both were feeding, and adult whales poo here because they feed opportunistically during the winter.

I know which option I’m betting on, but I’ll leave you to ponder the poo puzzle while I head to the airport to pick up more friends.

Related Posts:

Humpback Whales in Tonga 2013 | Part 1

Humpback Whales in Tonga 2013 | Part 2