Wisdom is an illusory concept. More often than not, we’re not aware of the wisdom we lack until we reflect on situations in hindsight. As such, the quantum of wisdom we possess often falls short of the level we actually require. It seems the fate of humanity to profit from experience mostly in retrospect, and to acquire wisdom as a consequence of folly. As Leonardo da Vinci put it, “Wisdom is the daughter of experience.”

Wisdom is an illusory concept. More often than not, we’re not aware of the wisdom we lack until we reflect on situations in hindsight. As such, the quantum of wisdom we possess often falls short of the level we actually require. It seems the fate of humanity to profit from experience mostly in retrospect, and to acquire wisdom as a consequence of folly. As Leonardo da Vinci put it, “Wisdom is the daughter of experience.”

I’d like you to keep this thought in mind as I tell you about my recent trip to learn about Australian sea lions (Neophoca cinerea) at Carnac Island, Western Australia.

Pinniped Primer

Australian sea lions are pinnipeds (literally, “winged feet”) — marine mammals whose closest living land relatives are bears. Pinnipeds comprise seals, sea lions and walruses, all of which are sleek, muscular and highly agile carnivorous animals that prey on fish, squid, shellfish and other similar fare.

Australian sea lions are pinnipeds (literally, “winged feet”) — marine mammals whose closest living land relatives are bears. Pinnipeds comprise seals, sea lions and walruses, all of which are sleek, muscular and highly agile carnivorous animals that prey on fish, squid, shellfish and other similar fare.

Like other pinnipeds, Australian sea lions can appear somewhat clumsy on land, a stark contrast to the grace and skill they display in the water. These animals don’t so much “swim” as they do “manoeuvre” through the sea, executing flips, twists, turns, sudden starts and stops, and other gymnastic feats at blindingly high speed and with incomprehensible precision.

All told, there are an estimated 12,000 or so Australian sea lions these days, with the population appearing to hold steady, or possibly to be diminishing gradually. They’re found only in Australia, mostly in the south and west, though there are sightings in other parts of the country as well.

The sea lions are listed under Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 as “Vulnerable” and South Australia’s National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 as “Rare”. In Western Australia, the aquatic mammals are designated as “In need of special protection” under the Western Australia Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 and also mentioned in the Wildlife Conservation (Specially Protected Fauna) Notice 2003.

Mature males are brownish in colour and grow up to two metres or so in length, tipping the scales at up to 300 kilograms. Females are less bulky, weighing in at about 80 kilograms at one-and-a-half metres in length. They also tend to be lighter in colour, sort of ash-grey on top and yellow/ cream on the bottom.

The sea lions that visit Carnac Island are all males, ranging from young pups to 300-kg craggly old bulls. They spend much of their time at sea feeding — several days at a time in fact — and then “haul out” onto the beach for a good snooze. This rest period lasts for a few days, during which time the sea lions’ primary mission is to rest and digest. What a life.

The sea lions that visit Carnac Island are all males, ranging from young pups to 300-kg craggly old bulls. They spend much of their time at sea feeding — several days at a time in fact — and then “haul out” onto the beach for a good snooze. This rest period lasts for a few days, during which time the sea lions’ primary mission is to rest and digest. What a life.

Australian sea lions are unique in a number of ways. Since pinnipeds breed on land but spend much of their time at sea, most species have highly synchronised breeding cycles to ensure everyone everywhere mates at the same time. Australian sea lions do not.

Dominant males of many pinnipeds establish harems at breeding time. Australian sea lions do not.

Other pinnipeds follow an annual breeding cycle. Australian sea lions do not.

They are, in a sense, the non-conformists of the pinniped world, a trait that complicates efforts to study and understand them. Speaking of which, there doesn’t actually seem to be very much known about these animals.

Not a lot of research, in the sense of studying the animals for the sake of studying them, seems to have taken place over the years.

So perhaps what truly characterises our relationship with these animals is our relative dearth of knowledge about them.

Making Contact

Swimming among Australia sea lions is an experience never to be forgotten.

Picture yourself in clear, shallow water, with white sand on the bottom alternating with patches of sea grass. There’s sun and blue sky above, sea birds calling through the air.

A slumbering sea lion stirs on the beach and waddles to the sea. Headfirst, it plunges into the water, slipping through the surf with the grace of a ballet dancer. You follow the dark form of the sea lion easily against the lightly coloured sand. You stand up in the shallow water, make a few splashing sounds with your fins, and quicker than you can pull your mask over your face, there’s a cuddly curious sea lion — frizzy whiskers and all — just a few centimetres away from you.

A slumbering sea lion stirs on the beach and waddles to the sea. Headfirst, it plunges into the water, slipping through the surf with the grace of a ballet dancer. You follow the dark form of the sea lion easily against the lightly coloured sand. You stand up in the shallow water, make a few splashing sounds with your fins, and quicker than you can pull your mask over your face, there’s a cuddly curious sea lion — frizzy whiskers and all — just a few centimetres away from you.

Duck your head under the water, and you notice that it’s a young pup, perhaps three to four years of age, mostly blond-beige coloured, with big chocolate-brown eyes that melt your heart. What you see reminds you of an inquisitive Labrador retriever puppy. Nose-first, the sea lion glides toward you, veering at the last second in a graceful loop, flapping his front flippers to propel himself through the water in a big arc and ending up right in front of you again.

Around and around the sea lion goes. Soon you’re joined by another sea lion, this time an older bull, which doesn’t move quite as frenetically as the young pup, but still displays the trademark curiosity of these animals. Staying near the surface, he floats toward you, occasionally sticking his nose out of the water to breathe.

Around and around the sea lion goes. Soon you’re joined by another sea lion, this time an older bull, which doesn’t move quite as frenetically as the young pup, but still displays the trademark curiosity of these animals. Staying near the surface, he floats toward you, occasionally sticking his nose out of the water to breathe.

You jump in surprise as the younger sea lion unexpectedly appears underneath, confronting you face-to-mask, giving you a quick kiss on the forehead, as if to say, “Welcome to my world.”

Determined to engage the playful pinnipeds, you swim frantically toward them. They respond by jumping clear of the water and splashing down next to you, taunting you to join them for a game of tag.

You try as best you can to keep up, but the sea lions are on home turf, and it’s all you can do to keep them in sight. When they disappear into the blue however, they almost always come back. Often, they’ll slow the pace down to let you catch your breath, resting on the sandy bottom to wait for you, watching you with their puppy-dog eyes.

The younger one rolls over on his back and wiggles from side-to-side to scratch his back in the sand, like a grizzly bear rubbing against a tree. It’s a comical sight, and you can’t help but laugh, releasing a stream of bubbles into the water. The pup looks up and responds in kind, with a burst of bubbles in your general direction.

The younger one rolls over on his back and wiggles from side-to-side to scratch his back in the sand, like a grizzly bear rubbing against a tree. It’s a comical sight, and you can’t help but laugh, releasing a stream of bubbles into the water. The pup looks up and responds in kind, with a burst of bubbles in your general direction.

Congratulations. You’ve just had your first sea lion conversation.

Sex Talk with Rick

One person that probably has more knowledge than the average bloke about these magnificent creatures is Captain Rick Reid, who owns and operates Sea-Reward, the charter boat that took us out to Carnac.

Originally a Kiwi (say it isn’t so!), Rick has been living in Western Australia for over two decades, and has been taking people to see the sea lions for nearly as long. Outgoing, friendly and highly observant, Rick is arguably not just a boat captain; he may be one of the best friends the sea lions have in Western Australia, if not the entire country.

Originally a Kiwi (say it isn’t so!), Rick has been living in Western Australia for over two decades, and has been taking people to see the sea lions for nearly as long. Outgoing, friendly and highly observant, Rick is arguably not just a boat captain; he may be one of the best friends the sea lions have in Western Australia, if not the entire country.

Rick’s been watching the sea lions here for so long that he arguably bears more than a passing resemblance to the pinnipeds he loves so much — mind you, the resemblance is more to one of the mature animals than the cute young pups. 😊

Departing from the city of Fremantle, we took about 30 minutes each day to reach Carnac. During my visit, I came to relish this daily transit time, as I peppered Rick with questions and quenched my thirst for knowledge at the fountain of his long experience with the sea lions. My conversations with Rick were instructive.

Among other things, I learned that the general consensus is that there may be around 300 males or so in the waters around Carnac and nearby islands like Seal Island, Rottnest, Little Island and others. On average perhaps 10% of the males are hauled out on the beaches at any one time, with the rest out foraging for food.

Among the most intriguing and mysterious issues we discussed was the problem of women — actually, given limited time and lack of alcoholic refreshment, we restricted ourselves to pondering problems posed by sea lion females only.

Among the most intriguing and mysterious issues we discussed was the problem of women — actually, given limited time and lack of alcoholic refreshment, we restricted ourselves to pondering problems posed by sea lion females only.

Recall that only males appear at Carnac and nearby islands. Any semi-curious person, of course, would ask where the females are. As if the Australian sea lions' general penchant for non-conformity weren’t perplexing enough, I learned that unique among Australian sea lions, the population of sea lions in this part of Western Australia is segregated by sex.

Females reside exclusively on islands somewhat to the north, in the Cervantes and Jurien Bay areas of Western Australia. They live there, give birth there, feed there and raise their young there. As far as anyone knows, they never party with the boys in Carnac.

Of course, boys will be boys, and every once in a while, they’ll feel the urge to beat one another up to establish pecking order, and then the males will move up north to court and breed with the females, more or less all at the same time.

But — and this I found really interesting — the breeding cycle isn’t annual. Females give birth on a 17.6 (+/- 0.3) month cycle, which is really weird. Females mate soon after giving birth, and they take care of their young for 15-18 months on average. The females also appear to cooperate to some extent in providing collective care for the pups.

In practical terms, this means that the breeding/ pupping cycle alternates seasons, instead of occurring at the same time each year, as is the more common pattern among pinnipeds. How the males know when to switch from eat-a-lot-and-lounge-on-the-beach mode to strut-your-stuff-and-get-the-girl mode also seems a mystery, given the considerable physical distance that separates the males and the females. Somehow or another, it all goes according to plan, and the male and female populations get together at just the right time to keep the show going.

To top off this list of odd traits, different colonies of Australian sea lions have different breeding times, i.e., they’re not synchronised, as I alluded to above. So one colony may be breeding and pupping, while another colony elsewhere may have no interest whatsoever in reproducing. Everything about the Australian sea lions’ breeding behaviour seems out-of-sync.

Why these sea lions exhibit such behaviour is anyone’s guess. We do know that Australian sea lion females don’t stray far from home, so at one point during our daily discourse Rick speculated that perhaps female populations in places like Carnac had been hunted to extinction, forcing males associated with such populations to look for companionship elsewhere. (Remember, males move around; females don’t — meaning that the females are much more vulnerable to excessive hunting.)

Why these sea lions exhibit such behaviour is anyone’s guess. We do know that Australian sea lion females don’t stray far from home, so at one point during our daily discourse Rick speculated that perhaps female populations in places like Carnac had been hunted to extinction, forcing males associated with such populations to look for companionship elsewhere. (Remember, males move around; females don’t — meaning that the females are much more vulnerable to excessive hunting.)

It’s not that far-fetched a thought, given that Carnac was used as a whaling station in the 1800s, and that there do seem to be eyewitness accounts of females living on Carnac and other nearby islands in the past.

Perhaps then, the unique system of sexual segregation among these sea lions is a relic of humanity’s colonisation of the area.

Sealed with a Kiss

One of the most incredible experiences I had was making friends with a particular sea lion. The encounter started like any other, with the pretty pinniped coming into the water from the beach, meandering among the people standing in the water.

Visibility in the shallows wasn’t so terrific; waves were stirring up the fine sand, and bright summer sunlight was reflecting off the particles. So I did my best playful-sea-lion imitation, swimming at high speed, doing loops in the water, launching myself out of the water and splashing back down — generally acting like a fool.

It worked. The sea lion turned its attention to me, so I gradually led the sea lion out to slightly deeper water (but still only two- to three-metres deep), where visibility was better and it was easier to play.

It worked. The sea lion turned its attention to me, so I gradually led the sea lion out to slightly deeper water (but still only two- to three-metres deep), where visibility was better and it was easier to play.

Everyone else followed, and though the sea lion played with everyone, it spent a disproportionate amount of time with me.

I had watched sea lion behaviour closely for the past couple of days, particularly the way the animals interacted with one another, and I was making a concerted effort to copy their behaviour. My efforts at sea lion mimicry seemed to pay off. To what extent the sea lion understood what I was “saying” I’m not sure, but at one point, the sea lion planted a big wet kiss on my mask, the first of many that morning.

Australian sea lions often greet each other in this manner, and over the next hour or two, I received probably 100 kisses or more. In fact, I had enough time to take a few self-portraits with my sociable sea lion.

As an aside, I should mention that all the interaction with sea lions at Carnac is totally at the discretion of the sea lions. If the sea lions want to play, they play. If they want to sleep, they sleep (which they do a lot of). If they want to head out to sea and find more interesting playmates, that’s exactly what they do.

Challenges

Keeping things in perspective, it's important to note that the sea lions’ world isn’t all play and good times. They face a number of challenges.

For instance, Rick noted that overall numbers of sea lions in the area don’t seem to be increasing. He has over 20 years of experience with the sea lions, so that’s a highly useful data point. Other people I consulted concur with this observation.

Why isn’t the population growing? No one really knows.

Males are aggressive just before mating time, when they’re preoccupied with establishing pecking order. They pick up younger individuals and fling them through the air to show dominance, so they’re clearly capable of violence at times, despite their adorable visages and normally tranquil dispositions. Perhaps injuries inflicted in this process contribute to the problem?

Or perhaps food supply is limited, thereby placing a restriction on the ability of the sea lions to grow in numbers? Pup mortality seems to be a significant issue too, though it’s difficult to say precisely what contributes to pup deaths. Inquisitive as they are, some find themselves trapped in fishing nets and crayfish pots, suffocating to death in the process. Others no doubt fall prey to sharks, and still others have been found choked to death by plastic rings used to hold soda cans together. Some have even been found shot, most likely by fishermen who view sea lions as competition.

Responsibility in Western Australia for protecting the sea lions and their habitat falls to the Department of Environment and Conservation, which was established on 1 July 2006, bringing together the previous Department of Conservation and Land Management, or “CALM” for short, and the Department of Environment.

Most people I talked to still refer to the responsible parties as CALM, so for the purposes of this discussion, I’ll use this acronym to refer to the parties within the Department of Environment and Conservation who have purview over the fate of the sea lions of Carnac Island.

At the top of the list of CALM’s published objectives is this: "Conserving Biodiversity – Protect, conserve and, where necessary and possible, restore Western Australia’s biodiversity."

A noble pursuit if ever there was one, and one which CALM seems to have taken action on in the context of Carnac Island.

For instance, CALM has recently implemented restrictions that prohibit passengers on charter boats visiting Carnac from going up on the beach, the intention being to minimise disturbance to sea lions and other wildlife on the small island. Carnac is, after all, only about 10 kilometres from Fremantle, so quite easily accessible to, and quite popular among, charter boats operating in the area.

For instance, CALM has recently implemented restrictions that prohibit passengers on charter boats visiting Carnac from going up on the beach, the intention being to minimise disturbance to sea lions and other wildlife on the small island. Carnac is, after all, only about 10 kilometres from Fremantle, so quite easily accessible to, and quite popular among, charter boats operating in the area.

CALM has also installed a solar- and wind-powered webcam on the island to monitor this policy in real-time. With such vigilance and well-intentioned measures, the sea lions should have nothing to worry about, right?

Think again.

Of Boats, Picnics and Kite Surfing

Carnac Island is an extremely popular destination for boaters from the mainland. It’s close to the city. It’s safe. Waters are shallow. There’s good snorkelling and fishing. In short, it’s an ideal spot for a weekend getaway.

Which is precisely the problem.

What you get on hot summer weekends is a mass congregation of recreational boats at Carnac Island, with everyone looking to have some fun, relax and gain some respite from the summer heat.

This in itself isn’t the issue, but for whatever reason, CALM’s regulations restricting access to the beach appear only to be enforced in the case of charter boats — at least that’s what I personally witnessed.

During the Friday, Saturday and Sunday I was at the island, there were over 70 recreational boats anchored in the small bay at one point (a complete madhouse), with people doing silly things like:

- Driving boats up onto the beach and straight into rows of sleeping sea lions

- Parents taking kids on the beach and encouraging their kids to throw rocks at the sea lions

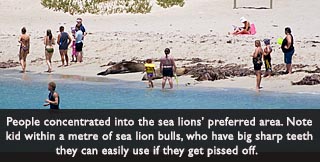

- Parents sticking two- to three- year-old kids in front of large male sea lion bulls (who have big, sharp teeth that could snap a kid in half without a second thought) for family snapshots

- People playing cricket on the beach and launching cricket balls at the sea lions

- People having picnics next to signs with warnings to stay off the beach under threat of heavy fines (All the signs are in English, so I assume everyone on the beach could read them. I watched many people read the signs, then ignore them.)

That’s not an exhaustive list of the crazy things I saw, but you get the idea. Hundreds of people harassing the sea lions, and some putting themselves and their kids in danger.

That’s not an exhaustive list of the crazy things I saw, but you get the idea. Hundreds of people harassing the sea lions, and some putting themselves and their kids in danger.

The ironic thing is that the passengers aboard the few charter boats at the island, including our boat, obeyed the rules and didn’t go ashore. That’s right. Under current interpretation and application of CALM regulations for Carnac Island, paying tourists — people like us who really care about the sea lions and their environment — are not allowed to step on shore to take photographs of sea lions, on the assumption that doing so would cause undue stress to the sea lions. Local residents, on the other hand, are free to throw keg parties on the beach and launch projectiles at sea lions. Talk about a perverse situation.

Two CALM representatives dropped by the island on Saturday and Sunday, walked around the beach and had friendly chats with some of the people committing obviously egregious offences, then left. As soon as they departed, everyone went back to what they were doing. Very effective.

Two CALM representatives dropped by the island on Saturday and Sunday, walked around the beach and had friendly chats with some of the people committing obviously egregious offences, then left. As soon as they departed, everyone went back to what they were doing. Very effective.

In one particularly astonishing and surreal instance, a man unpacked and assembled a five- to six-metre kite on the island, one of those humongous kites used for kite surfing. I happen to think kite surfing is really cool, but putting together a large kite like that just metres away from sleeping sea lions?

Luckily, the CALM guys were there and one went to have a chat. The CALM person pointed the kite-surfer in the direction of the sea, then got back on his boat and left. The kite-surfer finished putting together his kite and dragged it off in the direction the CALM representative had indicated — directly on top of and over 10 or more sleeping sea lions, scaring them half-to-death! I’m not sure what the CALM guy told Kite Man, but it looked almost as if he showed him where the sea lions were, so Kite Man could drag the enormous kite right on top of the slumbering sea lions.

Now, in what wild stretch of imagination does this jive with CALM’s stated objective to “Protect, conserve and, where necessary and possible, restore Western Australia’s biodiversity.”???

As I first-time visitor to the island, I struggled to reconcile the massive disconnect between bureaucratic rhetoric and real-life implementation. And it really didn't sit well that I wasn't allowed to walk softly along the beach with a telephoto lens to take photos from a distance, but this clown was allowed — actually directed by CALM — to traipse directly through the middle of the sleeping sea lions with large kite in tow.

Webcam? What webcam? Fines? What fines?

Perhaps the best way to sum up this section is with a short video clip. What you’ll see in the clip below is CALM’s attempt to set up a sanctuary for the sea lions [and fairy terns (Sterna nereis) — over 100 breeding pairs were chased off the island by rampaging boaters in recent weeks, thus prematurely ending the birds' breeding season, but that’s a whole ‘nother story].

To CALM’s credit, setting up a sanctuary is a step in the right direction, but what CALM seemed to have forgotten to do in the process is consult the sea lions.

As you’ll see in the video, the sea lions congregate at one end of the beach, while the sanctuary has been set up at the opposite end of the beach. So what you have is a situation akin to throwing a party without any guests — empty beach.

Worse, when the CALM representatives do show up at the island, they nudge people out of the sanctuary (where there are generally very few sea lions, if any at all) and force them into the non-sanctuary area (which is generally packed with sea lions) — yet another perverse outcome of bureaucracy out of touch with reality.

Worse, when the CALM representatives do show up at the island, they nudge people out of the sanctuary (where there are generally very few sea lions, if any at all) and force them into the non-sanctuary area (which is generally packed with sea lions) — yet another perverse outcome of bureaucracy out of touch with reality.

The result, as you'll see, is families and kids playing in front of resting sea lion bulls — a potentially dangerous situation, especially as mating season approaches and testosterone levels increase. As cute as they are, sea lions are wild animals, not petting-zoo exhibits.

Staying CALM

To be fair, CALM undoubtedly has many of responsibilities, and they have made efforts to establish a management plan for the island. Having a webcam is better than not having one. Establishing a sanctuary (albeit a seemingly ineffective one) demonstrates concern. Patrolling occasionally is better than not patrolling. And my bet is that CALM is more than likely short of resources, time, funds, labour and expertise.

But after spending a week at Carnac Island, it became painfully obvious that CALM’s efforts to manage the island and its wildlife fall short of what’s needed.

There’s minimal monitoring of visitors, and the convoluted restrictions that are in place forbid experienced charter boat operators and paying customers (who are the people who care the most about the animals and are least likely to disturb sea lions and other wildlife) from interaction, yet allow any yahoo and his mates to beach their boats, kick sand in sea lion faces, drag enormous kites over them, sick their 2-year old rugrats on them, hit cricket balls in the their general direction, and otherwise do anything possible to harass the sea lions, fairy terns, and any other intelligent life on the island.

There’s minimal monitoring of visitors, and the convoluted restrictions that are in place forbid experienced charter boat operators and paying customers (who are the people who care the most about the animals and are least likely to disturb sea lions and other wildlife) from interaction, yet allow any yahoo and his mates to beach their boats, kick sand in sea lion faces, drag enormous kites over them, sick their 2-year old rugrats on them, hit cricket balls in the their general direction, and otherwise do anything possible to harass the sea lions, fairy terns, and any other intelligent life on the island.

If there’s anything positive to be gained from all this, it would be if the relevant people in CALM could read this, and find some way to address these issues in a constructive manner. In the spirit of being constructive, here are a few suggestions:

- If you’re going to restrict passengers on charter boats from accessing the beach, then close the beach entirely and/ or implement a restricted-access system. It doesn’t make sense to keep the most educated, most caring people away, while permitting every yokel with a boat to have a beach party among the sea lions. Most paying tourists would be more than happy to contribute some funds toward the conservation of the island in exchange for supervised on shore visits (of very limited numbers of people) to see and photograph the sea lions.

- Use the webcam. I assume the webcam is there for a purpose. While I was there, many, many people strolled right in front of the webcam into the sanctuary, with no adverse consequence.

- If you’re going to create a sanctuary for the sea lions, maybe you should ask the sea lions which part of the beach they prefer. Even after a single day, it was obvious to me that there were nearly no sea lions in the designated sanctuary area, and tonnes of sea lions on the other side of the beach. Of course, since recreational boaters are permitted to go up on the beach that’s not designated as a sanctuary, the existing division of the beach actually has the counterproductive effect of concentrating people into the area preferred by the sea lions, thereby maximising the disturbance caused to the animals and potential danger to people. I’m sure that’s not your intention.

- If you threaten people with fines, then levy the fines when you catch people intentionally controverting protected areas. It does no good whatsoever to issue a threat and not follow through, because people will ignore the warnings, as appears to be the case now.

- Educate people. All you have to do is ask, and I’m sure people in the media will help you spread the word about the reasons behind the need for protection, both for the animals, and for people (i.e., those kids who have the misfortune of being born to parents stupid enough to leave them unattended in front of large wild animals with big sharp teeth).

Wisdom Revisited

Step back for a second, and consider that our history with many animal species has not been good. Dodos, stellar sea cows, baiji dolphins and Tasmanian tigers (to name but a few) are all animals that paid the ultimate price from humanity’s inability to learn. The same story — with places, dates, names and animal species interchanged — has been told over and over again — Extinction at human hands. As Yogi Berra once quipped, “It's like deja-vu, all over again.”

Fortunately for Australian sea lions, the situation doesn’t seem to be so dire…yet. No one’s arguing that these lovely animals are on the cusp of extinction, but then again, is it really necessary to wait until it’s that late? The argument that only animals on the verge of becoming extinct require protection is a spurious one.

Fortunately for Australian sea lions, the situation doesn’t seem to be so dire…yet. No one’s arguing that these lovely animals are on the cusp of extinction, but then again, is it really necessary to wait until it’s that late? The argument that only animals on the verge of becoming extinct require protection is a spurious one.

With 12,000 or so Australian sea lions spread across 70+ known breeding sites in Australia, there’s time yet to learn from experience and take measures to ensure the long-term well-being of these unique pinnipeds. Australian sea lions are a treasure worth protecting.

Within this context, the sea lions at Carnac Island might seem a drop in the bucket. At any one time, there might be 20 to 30 male sea lions hauled out on the beach, representing that portion of the population that happens to be taking a break from feeding.

But I suppose the real issue is this: There’s nothing, except perhaps apathy or lack of effort, to prevent us from collectively finding a way to manage Carnac Island and associated wildlife in a more rational manner than the current situation.

The ideal outcome would be to give the sea lions enough breathing space to go about their routine undisturbed, while still allowing people to continue visiting the island — boaters and tourists alike.

While visiting Western Australia, I heard stories about difficulties that CALM has experienced in the past when trying to implement measures to protect other animals and land. Specifically, CALM has found itself on the butt-end of public outcry in the past, and understandably, may be hesitant to take heat again.

While visiting Western Australia, I heard stories about difficulties that CALM has experienced in the past when trying to implement measures to protect other animals and land. Specifically, CALM has found itself on the butt-end of public outcry in the past, and understandably, may be hesitant to take heat again.

So CALM — if you’re reading this — here’s my plea to you to take seriously your pledge to “Protect, conserve and, where necessary and possible, restore Western Australia’s biodiversity” in the context of the sea lions of Carnac Island.

In that light, let me close with a thought from Mark Twain to help put things in perspective:

“We should be careful to get out of an experience only the wisdom that is in it — and stop there; lest we be like the cat that sits down on a hot stove-lid. She will never sit down on a hot stove-lid again — and that is well; but also she will never sit down on a cold one anymore.”

In other words, wisdom, as da Vinci pointed out, may be the daughter of experience, but only if you draw the correct conclusions from your experience.

Final Thoughts

Six days with the Australian sea lions was not enough. I’ve found myself thinking about them several times a day, every day. Thinking about swimming with them, being kissed by them, and of course, thinking about how they’ll fare next weekend, when there’ll no doubt again be scores of people treating the beach and sea lions at Carnac Island like a ride at Disneyland.

Hopefully, with CALM's help, the situation will improve in the near future.

If you’d like to pay a visit to these wonderful animals, it’s best to check in advance whether they’ll be there. Remember — the male sea lions disappear from time-to-time to visit the female sea lions. It wouldn’t be much fun to show up and find that no one’s home.

This is a relatively easy wildlife experience. You just need to be able to snorkel and not panic in the water. Most of the time, you’ll be in water shallow enough that you can stand up, and the little bay in front of the beach is well protected. The water is somewhat chilly, but I was completely fine spending hours in the water with a 5-mm suit and a hood.

Of course, the better you are at snorkelling and swimming, the more likely that you’ll attract the attention of the sea lions. The sea lions enter and exit the water when they want, so you’ve got to keep them interested once they’re in.

Of course, the better you are at snorkelling and swimming, the more likely that you’ll attract the attention of the sea lions. The sea lions enter and exit the water when they want, so you’ve got to keep them interested once they’re in.

To check on the sea lions' schedule and make bookings with Rick, contact the West Australia Dive Centre in Perth. If you visit, make sure to say hi to Rick and the sea lions for me.

I can’t get enough of the sea lions, so I’ll definitely be going back. If you’d like to join me next time, drop me a line via my contact form. I’ll be more than happy to show you how to behave like an immature sea lion.