A heckuva lot happened this week. The short version: Yo-yo whales on Sunday; a fascinating discovery on Tuesday that a female with a calf last year is back now with a new calf; a few hours with a male and female pair engaged in courtship on Wednesday; more of the mother with consecutive calfs and the mating pair on Thursday; three other calfs and an encounter with a yearling on Friday; heat run on Saturday.

Read on for the extended version.

What Goes Down, Must Come Up

On Sunday, Takaji and I had a rare chance to go out to look for whales by ourselves. In fact, every other day that we're in Tonga this season, we have groups of people with us, so the beginning of this week was the only chance we had to get in the water and concentrate just on photography.

With only ourselves to look after, we decided to try for relatively difficult whales...the yo-yos. When most people visit Vava'u for whale watching, they want to see mothers with newborn calfs. Perfectly understandable. Humpback whale calfs are adorable, and in many cases, the moms and babies can be relatively settled, such that it's not too difficult to get a good look at them. They are, so to speak, perfect tourist whales.

In the case of yo-yo whales, you've got to find them (not easy because they only come up for a few breaths and then dive deep again), keep an eye on them while they're down (again, not easy because humpbacks have countershading, i.e., dark dorsal surface area, so they tend to blend into the background), and then get yourself to the right place at the right time when they finally decide to come up for air (assuming they haven't pulled a fast one and snuck off without your noticing).

The one saving grace, of course, is that they always come up for air..."What goes down, must come up", to mis-paraphrase the old saying.

Over time, we've become pretty good at finding and observing whales like this, and for me at least, the challenge is something to relish.

At the bottom of the Hunga channel, we found several pairs of whales, with no other boats around. As is typical for yo-yo whales, each pair surfaced for a few breaths at a time, then dived down to perhaps 25 metres or so for 10 to 15 minutes, then came up again. The long waits were challenging given choppy seas and chilly water, but we managed to be in the right place at the right time on several occasions...making it a rewarding and relaxing day.

Calf Count

Our running total for the calf count we're keeping came to 15 by the end of week two, comprising six we're confident of being able to identify again using underwater photos, and nine which we either weren't able to get into the water with, or for which don't have sufficient images to make a positive ID.

One important sidenote is that this running total of fifteen doesn't include the calfs that Paul and Karen from Dive Vava'u have seen and recorded this season. There will no doubt be some overlap when I get information from them later about their sightings and integrate the lists, but I'm hopeful there will be a number of net additions as well.

The most exciting part of the calf count came on Tuesday, which was our first day out on the water with the groups of visitors who arrived on Monday. Early in the morning, we found a mom and calf that turned out to be reasonably friendly. As soon as I saw the large female in the water, I was hit by a strong sense of déjà vu.

Later in the evening, we confirmed that she was a female with a calf that we had seen, photographed and catalogued in 2008, which meant two important things: First, we demonstrated that a specific whale has visited Vava'u in consecutive years; and second, we can prove that she had babies in both years...an unexpected early payoff for going to the effort of documenting our mother and calf encounters.

Why is this important? It supports the notion that humpbacks in this region make repeat visits to certain areas, and it also goes some way to showing that any attention Lilo (the name we gave the mother) received last year in Vava'u while she had her baby didn't keep her stay away from the islands this year.

Over the years, I've heard many people proclaim that increased boat traffic has driven humpback whales from Vava'u and that allowing people to get into the water with whales is tantamount to harassment...the implication usually being that there will be no more whales left unless human activity is restricted and/ or banned. This is obviously a serious concern, and one that can't be brushed off lightly.

The thing is, I've never seen any data to support such assertions. It might exist; I've just never seen any. And often, the people making such statements have spent little to no time in Vava'u, and usually, they've spent none in the water observing whale behaviour.

Call me cynical if you will, but I trust the whales more than I do people. If Lilo sees fit to re-visit Vava'u with babies, she must feel comfortable here. Her return to Vava'u is a positive sign, one that argues for the ability of people and humpbacks to co-exist in harmony.

In any case, Lilo is just one example, so it's difficult to draw any definitive conclusions. I hope we can document more return visits in the future.

(See my earlier post about Lilo and her baby Stitches for more details.)

Besides Lilo, there were a couple of other calfs we named this week, namely Jaws and Curious George. We found both on Friday, along with another that was too active for us to get underwater images. Of the two, I found Jaws and Takaji found Curious George. I named Jaws after I saw the calf open its mouth while swimming alongside its mother.

I've seen baby whales open their mouths wide underwater, and adult humpbacks sometimes do something similar during heat runs, but this is the first time I've seen a baby open wide like this while swimming at the surface. Although Jaws is facing the opposite direction, you can clearly make out the baleen hanging from the top of the calf's mouth. I'm not sure what Jaws was trying to achieve, but it was cool to watch, and it made the task of picking a name for the calf really easy.

I'm still amazed that I managed to get photos, since the seas were acting up and I was being bounced, tossed, thrown, shaken and stirred in every which direction while trying to photograph little Jaws's jaws.

Takaji picked the name Curious George for the other new calf because his sons happen to be keen on the Curious George books right now, and the calf seemed particularly inquisitive.

Incidentally, the way we've been working things is that the person who finds and photographs a calf gets the naming rights. We only name a calf if we have underwater images, and only if those images are of sufficient quantity and quality that we're confident of being able to identify the relevant calf if we encounter it again in the future.

When possible, we also try to photograph the mom's unique features for future reference...something that proved invaluable in the case of Lilo.

Calfs: The Making Of

The courtship ritual between a male and female humpback is one of the most spectacular and moving sights I've ever witnessed. I'm not sure if the term "courtship ritual" is technically accurate, but it's difficult to think of a more appropriate phrase.

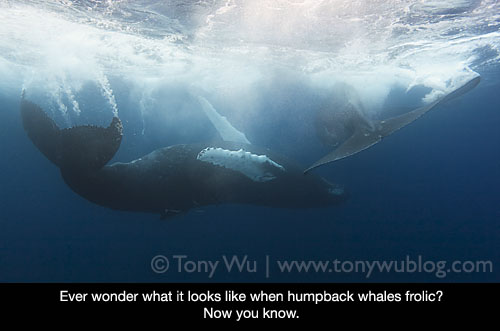

It goes something like this...Male and female whale hook up, decide they like each other, swim around together, stroke one another, rub their bodies together, caress each other gently, splash and cavort at the water's surface with obvious glee, dive down to the depths for some private time, emerge from the abyss to perform spectacular breaches...and so on.

I've been fortunate enough to see this several times, most recently on Wednesday.

When a pair of whales are in this romantic mood, they either completely ignore you (in which case, there's nothing to write about), or they size you up and then incorporate you into their activities. The first time I came across a mating pair, I had no idea what was going on. All I knew was that there were two whales swimming just ahead, and I really, really wanted to catch up to them. I went from huffing and puffing to keep pace with the whales...to suddenly and unexpectedly being right alongside them, with the whales swooping and swerving all around, as if they had decided to reward me for my effort.

Now that I've been through the routine a number of times, I know that the whales sometimes seem to test people who get into the water to see what you're made of. In this most recent experience, four of us entered the water, but I was the only one who kept up for the two to three kilometres of swimming in circles that ensued.

Everyone else got back on the boat and trailed behind as I did my best to stay with the frolicking cetaceans. At one point, perhaps 30 to 45 minutes after I had entered the water, the pair stopped without warning, waited for me to catch up, then started swimming again...adjusting their pace to accommodate my swimming speed.

The three people who were with me eventually dropped back in, and the whales treated all of us to an afternoon performance of some of most graceful and acrobatic manoeuvres you'll ever see from 80 tonnes of aquatic mammal.

Of course, the entire point of their activity is to make a cute little baby whale, so in a sense, we witnessed "behind the scenes, making of" clips of an upcoming calf's life.

After some time, the pair decided that playtime was over...and slipped off into the deep to continue their ritual. As far as I know, no one has actually seen humpback whales mate.

We happened upon the same pair again the following day. They were easy to identify, as the male's pectoral fins were white on both sides, which is an unusual trait here. The amorous couple were still at it...so clearly, courtship for humpbacks is something they enjoy and take their time with.

The Young and the Restless

On the way back into the main harbour on Friday, we saw a small spout.

On the way back into the main harbour on Friday, we saw a small spout.

Friday was a bonanza day for calfs: we found Jaws, Curious George and one more in the first few hours out, so naturally, the first thought that popped into our heads was, "Another calf!"

Something wasn't right though, since calfs should be accompanied by their mothers, meaning that small spouts should be followed by big ones. That's one tell-tale sign of a humpback whale mother and calf.

The only thing we could make out was a single, tiny blow, taking in five to seven breaths of air, then diving for relatively short periods of time. In each instance, the whale emerged some distance away from where it had dived, indicating that it was moving while it was submerged.

Possibilities ran through my head: Abandoned calf (we had an interesting experience with one in 2008)?; whale with a breathing problem?; a particularly stealthy mother?; a different species of cetacean?

As we approached, I indicated to everyone that I would go in alone to check the water, as the visibility was generally poor in the area concerned (just off Eueiki), and the whale was clearly moving around. Chances were, I wouldn't see anything, so I wanted to save everyone the trouble of getting in and out for nothing. All the same, I asked everyone to get geared up...just in case.

When the whale dived near us, I slipped into water with the intention of taking a quick peek and getting back on the boat.

Lo and behold, the whale had swum over to the boat and come to a complete stop about eight metres directly underneath me! As if that weren't enough, the visibility was incredible...crystal-clear blue water with perfect light from the afternoon sun.

I waved frantically for everyone to get it. The whale just sat there, clearly aware of our presence, but in no particular hurry to move on. It was small...not quite a calf, not quite an adult. It moved slowly toward us...not so much out of caution, but more, so it appeared, with curiosity. It rotated to get a better look at us, completing a full circle around us, then drifted up to take a few breaths and dived down again.

The little humpback did this three or four times, before executing a full breach and swimming away.

In hindsight, I think our encounter was with a calf that was recently separated from its mother. In other words, the calf had been raised successfully and had arrived in Vava'u with its mom, and was now on its own.

The reason I'm going with this theory is that the calf reminded me of two encounters we documented in 2008, with really large calfs we named Blade and Yankee (calfs 5 and 6 in last year's count). The whale we swam with on Friday was about the same size as those two calfs, and had similar morphology (shape).

Of course, I could be totally wrong, but the whale's size, shape and temperment all suggest this scenario.

Wrapping Up

So those are the highlights for the week. I haven't covered everything, but clearly, there was a lot going on over the past few days. The number of whales in the area seems to be picking up, as does the level of activity.

The most frustrating aspect of the week for me is that I haven't seen a heat run yet. Karen has seen three, and Takaji has seen one (so not fair!). It's great that the heat runs have finally started (or have come close to the islands where we can see them), but I so want to see one.

In case it isn't obvious...I love heat runs. Whales in a heat run are filled with adrenaline and testosterone. They transform from placid, gentle filter-feeders into snorting, snarling cetaceans. The action is fast, and the interaction sometimes violent. Heat runs are all about energy, and I'm completely addicted.

Sigh...perhaps next week.