Only a few days have passed since I was out on the water looking for humpback whales in Tonga, but it feels as if months have gone by. Strange how that’s always the way.

I’m sitting on a plane as I begin to write this, looking over my notes and images from the past couple of months. It’s been another fascinating season of observing and photographing humpback whales...an odd one in some respects.

For a start, the season was relatively wet, at least compared to last year. It rained on 40% of the days I was in Vava’u (21 out of 52 days). Not necessarily torrential downpours, just sprinkles on some days in fact, but at least some rain on each of those days.

It rained a bunch on the day I was scheduled to leave. So much, in fact, that my morning flight from Vava’u to Nuku’alofa was cancelled. Fortunately, the heavy precipitation let up by early afternoon, and I made it out with time to spare for my international flight (whew!).

More vexing than the rain though, was the overall climate. Many days in August were warmer and muggier than I would have normally expected, and the cool, crisp, clear days that generally characterise that time of year seem to have been pushed back to late September and early October.

Nuku’alofa was so cool during my brief stopover on the way home that I needed a fleece jacket just to keep from shivering…not normal at all. The southern hemisphere is headed into summer. It’s supposed to be warm by this time of the year.

For what it’s worth…I’ve encountered non-standard prevailing conditions just about everywhere I’ve been in 2013, from north-to-south, east-to-west: rains were early in Sri Lanka; winds were crazy strong in Baja; it was cool and rainy(!) in Western Australia; the ice never melted in the Canadian Arctic this summer; and then the flip-floppy conditions in Tonga.

As I noted at the beginning of the season, the visibility underwater was generally pretty good, at least until a 4-day period of sustained strong winds and big swells hit around 20 September, producing super sloppy seas.

An epic bloom of pink fuzzy things in the water also occurred in mid-September, which, when combined with the stirred-up sediment, resulted in a precipitous decline in visibility everywhere, including far offshore.

Bummer.

Also reminiscent of what I’ve experienced everywhere else in 2013…the general pattern of whale encounters seemed odd. Not necessarily bad. Just different.

There was a considerable level of activity early in the season, with multiple heat runs reported each week, daily breach sightings, lots of singers, etc. But...the action tapered off in early September, dropping to the point of nearly no activity by the third week of that month.

There was so little action toward the end of September that I began to think that maybe the females of this humpback population were finally taking a break after producing to many babies in 2011 and 2012. Perhaps, I thought, there were relatively few eligible and willing females this season, and they’d done their thing early on, then headed south.

If this were the case, the boys might hang out for a while longer, until they finally realised that there wasn’t much point sticking around much more, then move south as well. (Boys of any species can be a bit slow working things out, after all.)

For several weeks, this working “theory” made lots of sense and was entirely consistent with real-life observation.

The spanner in the works though, came on 4 October, when, for some inexplicable reason, lots of whales showed up.

On that day, we encountered at least two groups of three socialising whales, a mom/ calf/ escort, and several single whales, including at least one singer…all within visual range, all at the same time. After weeks of nearly no activity, we were literally surrounded and had no idea which whales to follow.

Go figure.

Plus, we saw other boats with whales, including what looked to be a heat run. A heat run!

The sudden bounty of boisterous baleens continued for a few days, capped off with a nice heat run involving a mother/ calf pair and three escorts on 7 October. The skies were dark and it was pissing down rain, but two of the escorts were engaged in epic battles involving lots of head-bashing, body-slamming, tail-swats and bubble-blowing. Quite a spectacle indeed.

Meanwhile, calf density remained high, even through the relative scarcity of whales through the mid- to late-season.

More specifically, even though there didn’t seem to be many active whales around for much of the season, there were still a lot of humpback whale mother/ calf pairs. Puzzling in a sense, as my experience over the years has been that calf density seems to track overall whale numbers.

In other words, lots of whales = lots of babies; while fewer whales = fewer babies.

This season demonstrated that sometimes, there can be an inverse relationship between overall whale numbers and the number of baby whales. There were relatively few whales, but calf density was high. Sort of makes me think I should figure out a way to track overall whale density in the Vava'u area going forward.

So...I know I said that I wasn’t going to do my calf count this season, but I sort of couldn’t help myself.

Keeping in mind that I took at two-week break in late August/ early September, and noting that I didn’t try as hard as I have in previous seasons…I did keep a record of my own calf encounters.

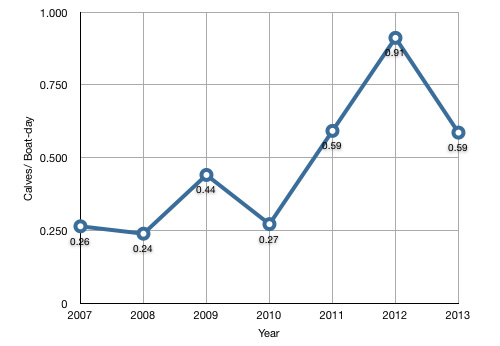

This year, I spent 29 days on the water looking for whales, during which I photo-ID-ed 17 unique mother/ calf pairs. That equates to a ratio of 0.59 calves/ boat-day, which is pretty darn high.

To put this in perspective, the equivalent ratio has ranged between 0.24 and 0.91 since I started doing my calf counts, with the high figure achieved in 2012, as reflected in the graph below.

My two-week vacation from 28 August to 12 September, during which time I did not look for or count humpback whale calves, may have had an effect on the data I collected, but if anything, past experience suggests that the ratio would’ve been the same or higher, not lower, had I worked during that period.

The reason? Late August/ early September has been peak calf-ID-period in past seasons. If there were a bell curve for appearance of humpback whale calves around Vava’u, with calendar dates on the X-axis and calf IDs on the Y-axis, my two-week break would fall smack within the peak.

A few other interesting observations about the whales this season…

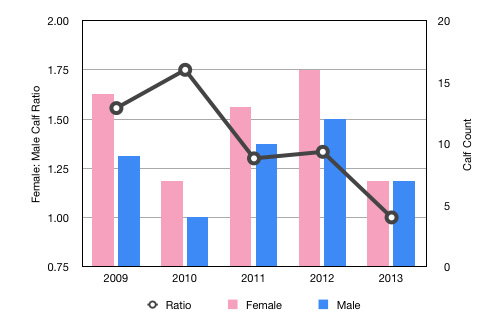

The ratio of female-to-male calves was a tie this year. Of 14 humpback whale calves for which I was able to determine sex, seven were female, and seven were male. As I reported in posts earlier in the season, the males actually led for a long time. But the females made a strong comeback at the end, pulling even.

I’m thinking that my truncated observation period affected this ratio, as females have outnumbered males for each of the past four seasons. My gut says that had I worked the full season, females would’ve outnumbered male calves once again.

The results of next year’s tally will therefore be all the more interesting. I am not planning to take a break mid-season in 2014, so if the females once again outnumber males, then I’ll have renewed confidence in the trend that the past four seasons have suggested. If we tie or males exceed females next year, then…well…back to the drawing board!

There didn't seem to be as many escorts accompanying the mother/ calf pairs this season as there have been in the past. The ratio of mother/ calf pairs that had one or more accompanying escorts when we happened upon them dropped from 0.63 in 2011, to 0.52 in 2012, and 0.47 this year.

I've only been tracking this figure for three seasons, so I'm not sure if there is or ever will be a meaningful pattern here. But the fact that there seems to have been a relative drop in escorts would seem to be consistent with my overall feeling that there were fewer whales around in general viz. recent breeding seasons. (There I go again...trying to apply logic.)

As best I can tell, I did not photograph any repeat mothers, i.e., female whales with calves this season that I photographed in previous seasons with babies. Recall from last year that the greatest number of calves that I’ve documented a single female bringing to this area to date is four babies, the mother of 201217 Juunana last year (also the mother of 200816 Chibi-chan; female calf 200929 Floppy; and a calf in 2002, which I ID-ed from a NatGeo documentary produced in 2009 (see humpback whale calf count 2012, page 34 for details).

I didn’t see/ notice many injuries this season, either among the calves or the humpbacks in general. In recent history, 2011 was the big injury year, when many calves had serious wounds, with male calf 201114 Tahafa being the standout. I’m assuming that whatever was around in 2011 attacking baby whales wasn’t around this season, or in 2012 for that matter.

Within this context, There were some whales that exhibited the scraping wound pattern that I’ve photographed and discussed before. The wounds look like what might result if you scrubbed a whale with steel wool or a Brillo pad: scratch marks with scraping away of skin and some surface tissue, but no deep injuries.

This type of injury pattern generally appears across the dorsal ridge between the dorsal fin and fluke, usually exhibiting bilateral symmetry (same on both sides of the body), for some odd reason.

This female calf (201314) had such scraping wounds, but only on the right side of her body. I’m hoping that someday I’ll be able to figure out what causes these injuries, but the time being, I haven’t a clue.

One adult, the mother of female calf 201317, had a prominent series of scars on her fluke and portions of her torso that came from an attack, possibly by either orcas or pseudorcas.

A few miscellaneous bits and pieces to wrap-up: There were a few white pecs around this season. I photographed two (one calf, one adult male), and I heard of 2–3 more. The total fell far short of the 20 I recorded last year though. There were no split dorsal fins as far as I’m aware.

When I step back for some perspective on this season, there are a couple of things that I know will stand out in the long run:

- The possible feeding sequence I described here and here. I still haven’t found any other references to feeding in the winter breeding grounds by humpback whales. Please let me know if you come across any.

- The star of the season, Jack and his mom, who were in the Vava’u area for at least nine days this season: 17, 18, 19, 20, 28, 30 September, and 1, 2, 3 October. It’s very likely that Jack and mom were in the area on 29 September as well, but no whale watching is allowed on Sundays in Vava’u, so I unfortunately can’t confirm that date.

Since I managed to photo-ID 17 mother/ calf pairs, I will probably put together a summary document in the following weeks, so I can have a record for ease of future reference, for things like comparing females across multiple seasons in order to look for repeat mothers, and to recall specific details like injuries, dates of encounters with Jack, etc.

Finally, I’m in the process of filling my schedule for the 2014 season. I’ve set dates and I’m currently working through the list of people who have contacted me previously. I’ll send out an e-newsletter and post to my trips page for any remaining spots after I’ve gone through this process.

If you’d like advance information about joining me for encounters with humpback whales next season, please send me a message via my contact form.

Bye for now!

Related Posts:

Humpback Whales in Tonga 2013 | Part 1

Humpback Whales in Tonga 2013 | Part 2