At the end of August, I spent more than a week in the ocean. At night. Swimming. Waiting. In vain.

Decades of working with Mother Nature has taught me to accept and adapt, not to fixate and bemoan.

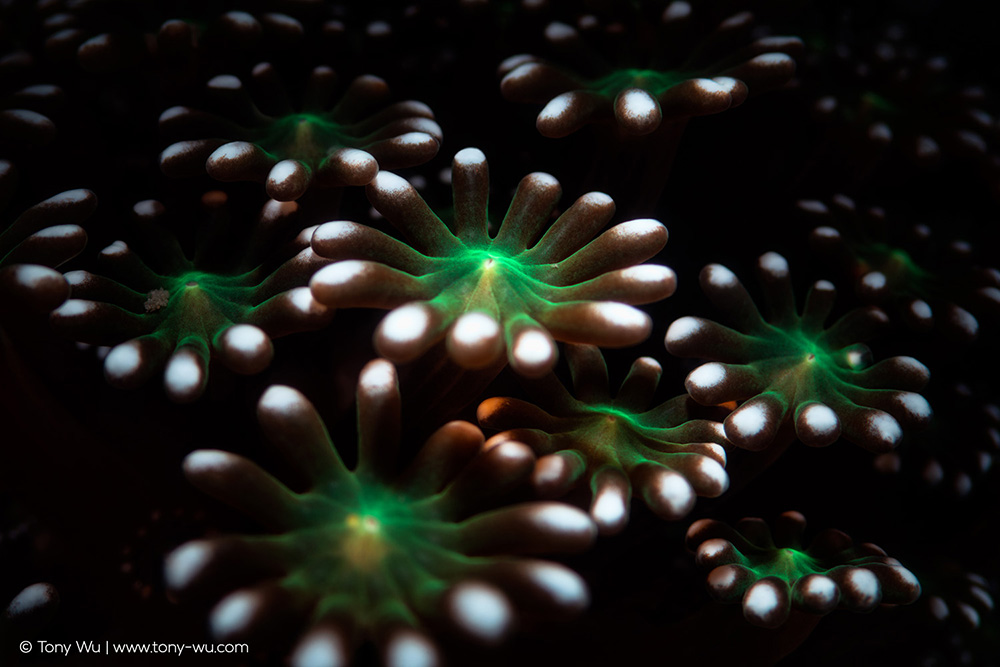

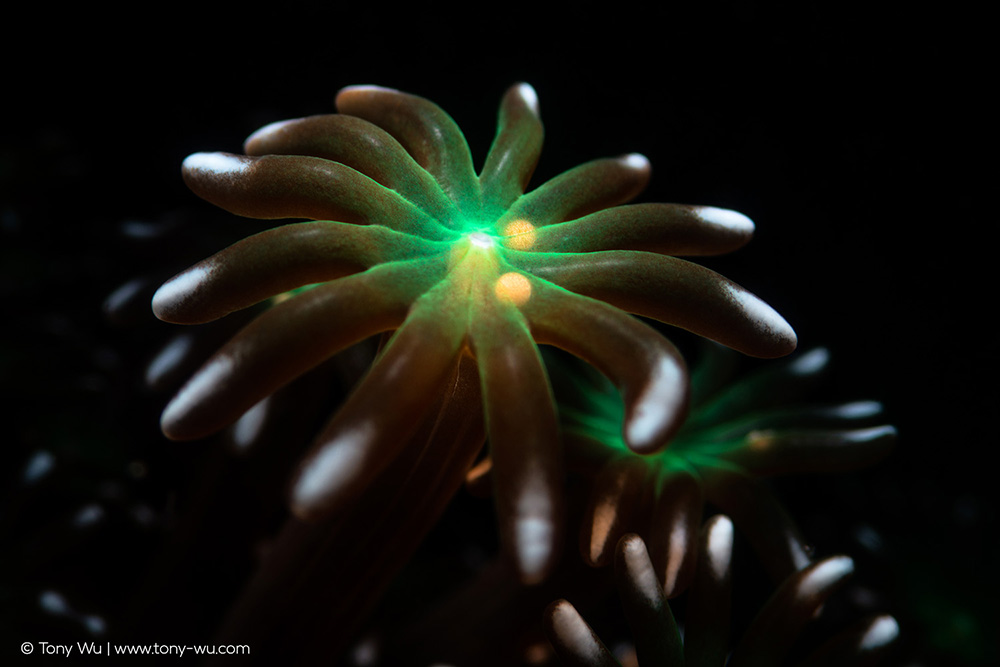

That is how I ended up photographing Alveopora japonica:

Believe it or not, this is a type of Acroporidae hard coral. That’s the same family of corals that comprises the staghorns that scuba divers see in warm waters. The corals’ stony structure lies beneath the field of pretty 12-tentacled polyps.

They don’t look like much in situ (fancypants-speak meaning “in the actual location”). Do an image search. You’ll see what I mean.

Local friends had been encouraging me for years to take a look, because one of the largest aggregations of this species in Japan—if not the largest—was nearby. I had never had the time (due to being preoccupied with other subjects), nor the interest if I’m being perfectly honest.

Failure often sparks creativity though.

With time and a plethora of under-utilised gear on my hands, I dreamt up a new illumination technique that I thought might show large coral polyps in their best light (that pun’s for you Bert.)

Like many brilliant ideas, this involved Scotch tape. Plus miscellaneous stuff that I’ve picked up over the years and somehow managed to retain despite being repeatedly instructed to “throw that junk away!”

It worked from the first try. I was as surprised as anyone.

The upshot is that I was able to isolate polyps from the visual clutter, to highlight each coral’s delicate structure, and even better, to show the developing planula (the orange orbs).

In case you aren’t familiar with the term, a planula is a free-swimming coelenterate larva with a flattened, ciliated, bilaterally symmetric solid body, i.e, it’s a baby.

Many corals send out gametes (eggs and sperm) into the water column. That’s what you will have seen with footage of staghorn coral spawning, for instance. This species sends out babies, which ideally float and swim, then settle and grow. I haven’t devoted much time to reading up on the ins and outs of planulae (plural of planula). There is undoubtedly more to the process.

But the point here is: “Whoa, isn’t that cool?” (asked in the most gee-whiz scientificky voice possible).

I later learned that this species is found throughout the northwest Pacific, with aggregations documented in the waters of Japan, Taiwan and Jeju island in Korea.

DNA analysis of corals and their dinoflagellate endosymbionts (I’m just full of fancy words today) from these areas suggests that substantial time has elapsed since divergence of these populations—so much so that classification into separate species may be warranted. (1)

Sometimes failure can be a good thing. It just depends on how you look at it.

(1) Kang JH, Jang JE, Kim JH, Kim S, Keshavmurthy S, Agostini S, Reimer JD, Chen CA, Choi K-S, Park SR and Lee HJ (2020). The Origin of the Subtropical Coral Alveopora japonica (Scleractinia: Acroporidae) in High-Latitude Environments. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8:12. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.00012